The procession for the Festival of Sant’Efisio in Calgiari is one of the most spectacular – and authentic – religious festivals in Italy, and a celebration of Sardinian folk culture.

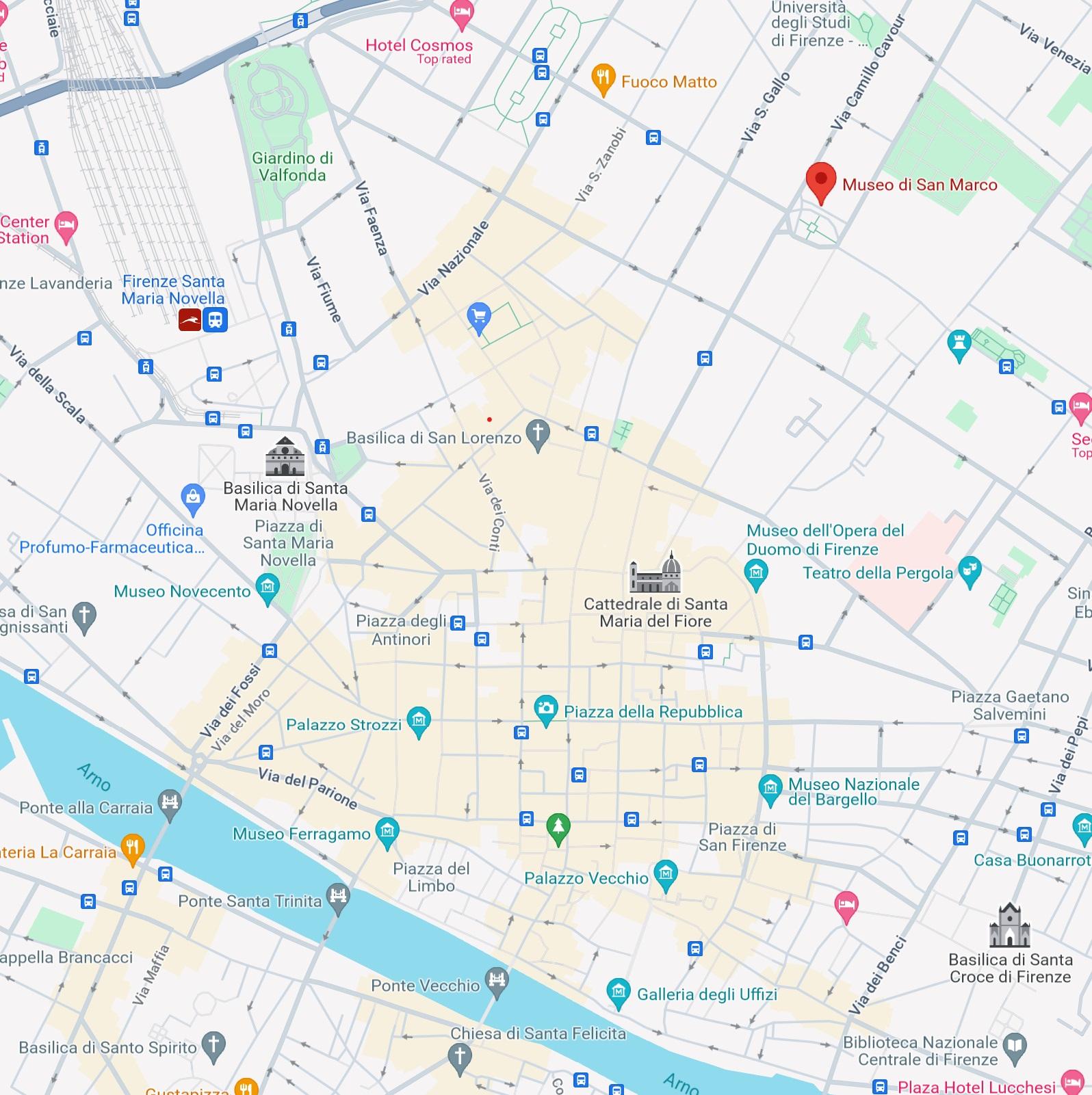

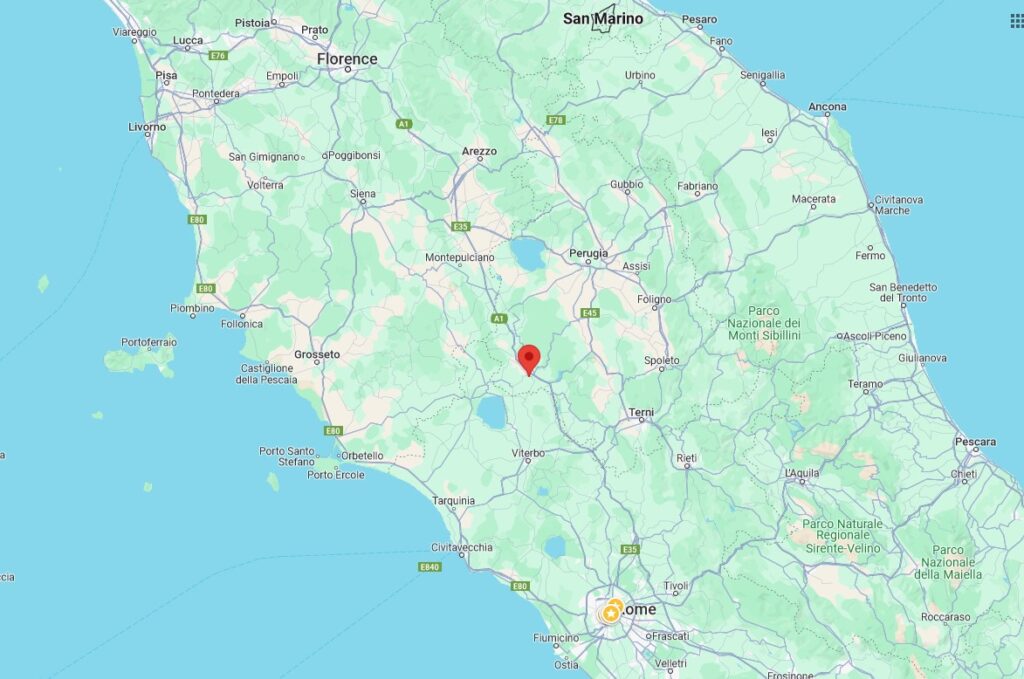

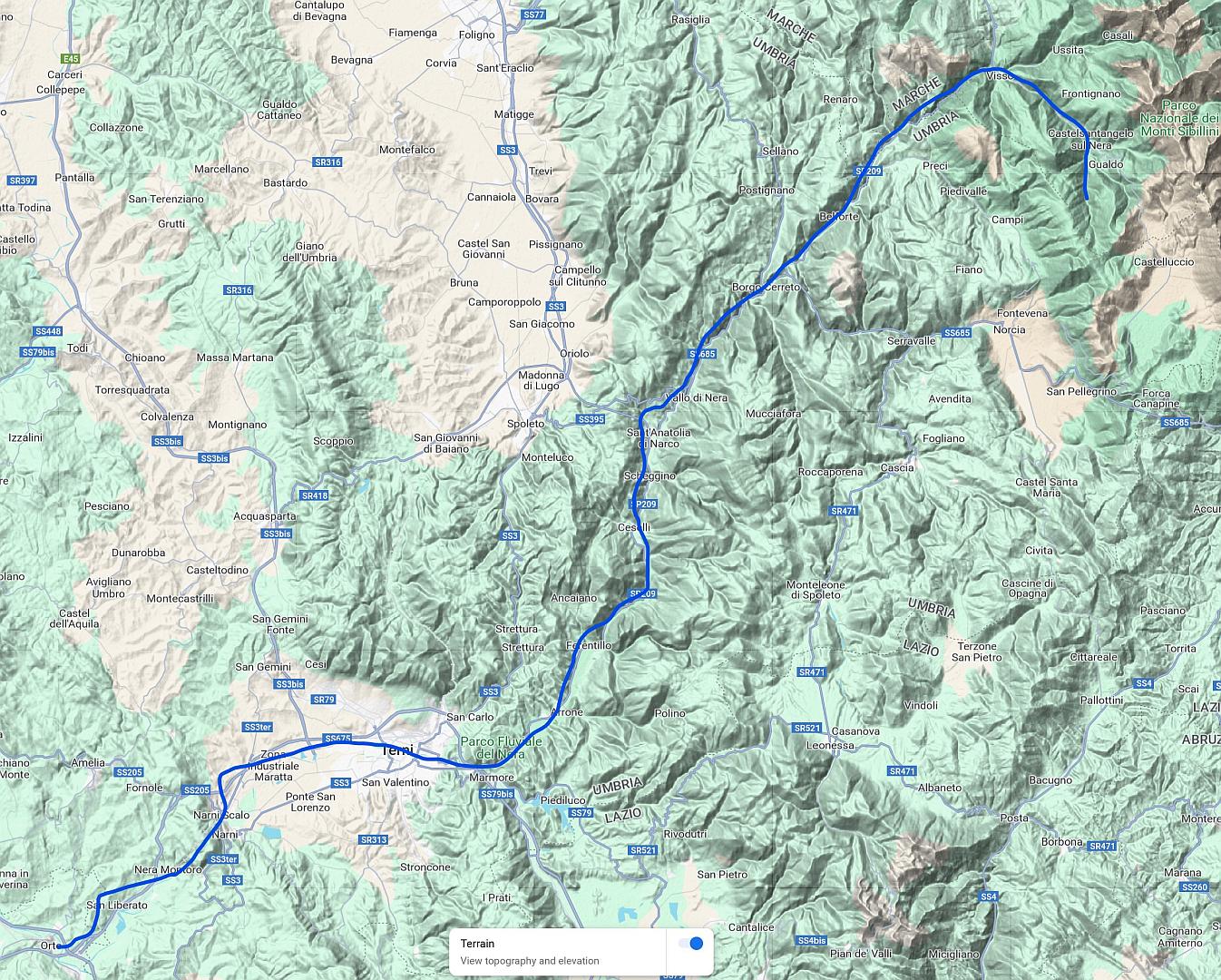

In 25 years of visiting Italy, and more recently of living here for part of each year, there was one region of the country that we had yet to set foot in – Sardinia. So in May 2025 we finally rectified that, and took the overnight car ferry from Civitavecchia to Olbia for a ten-day visit.

First Impressions of Sardinia

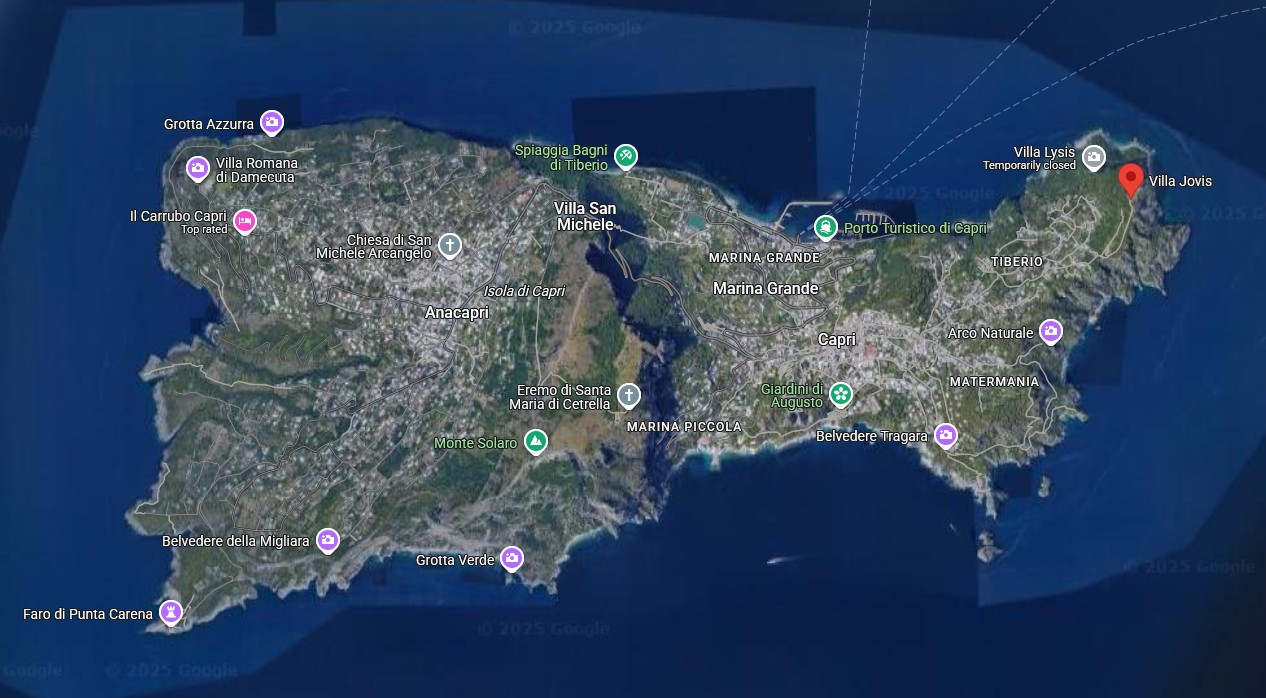

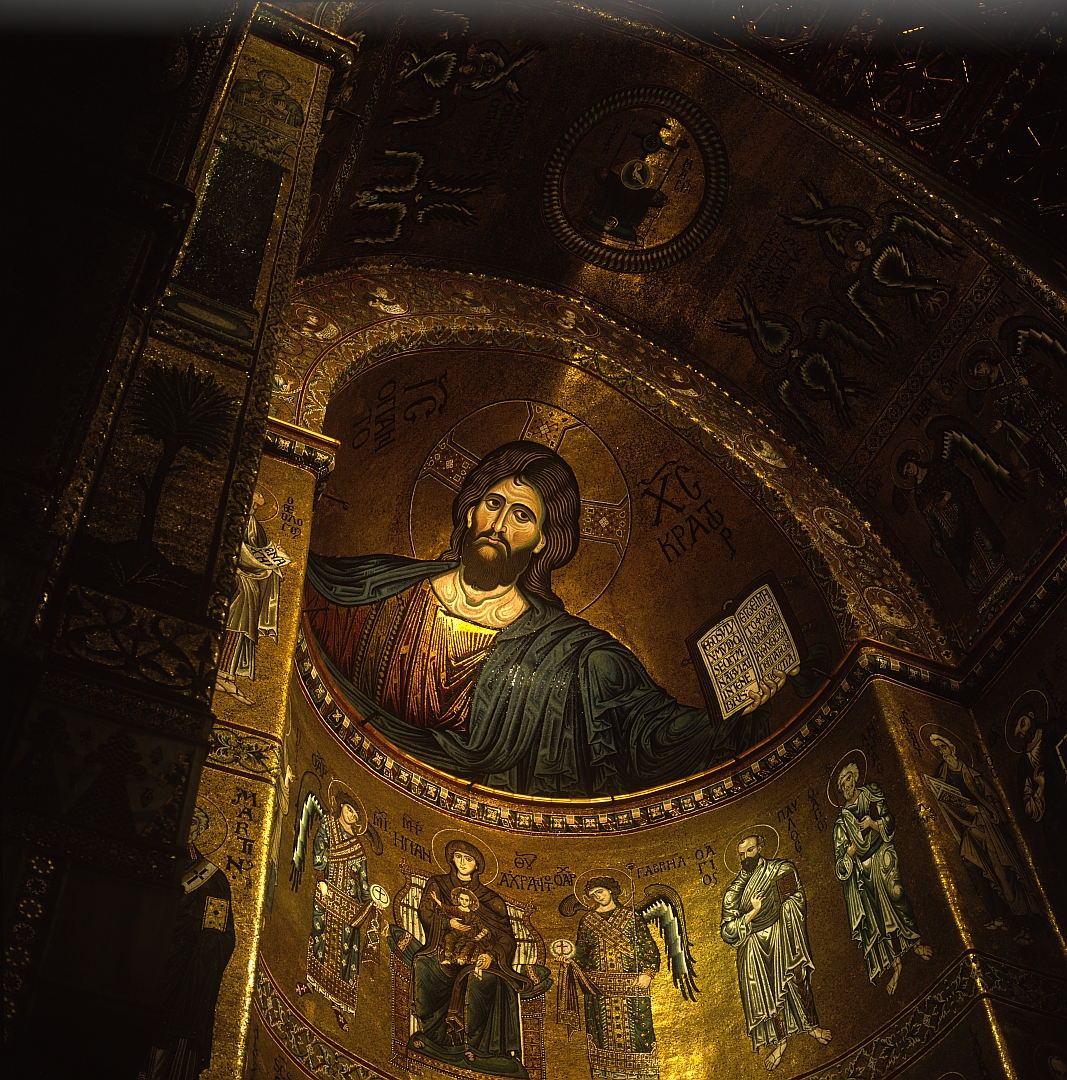

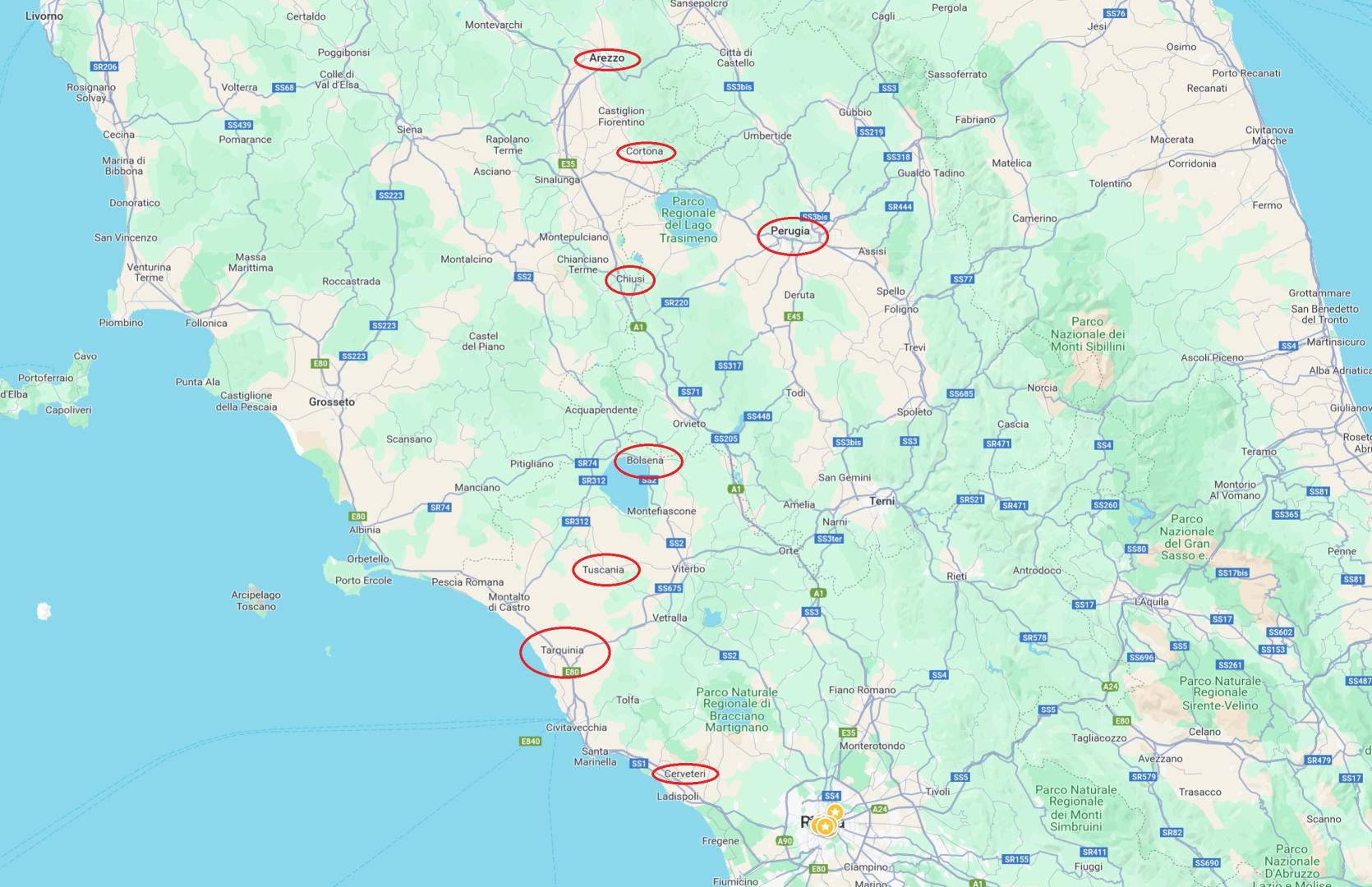

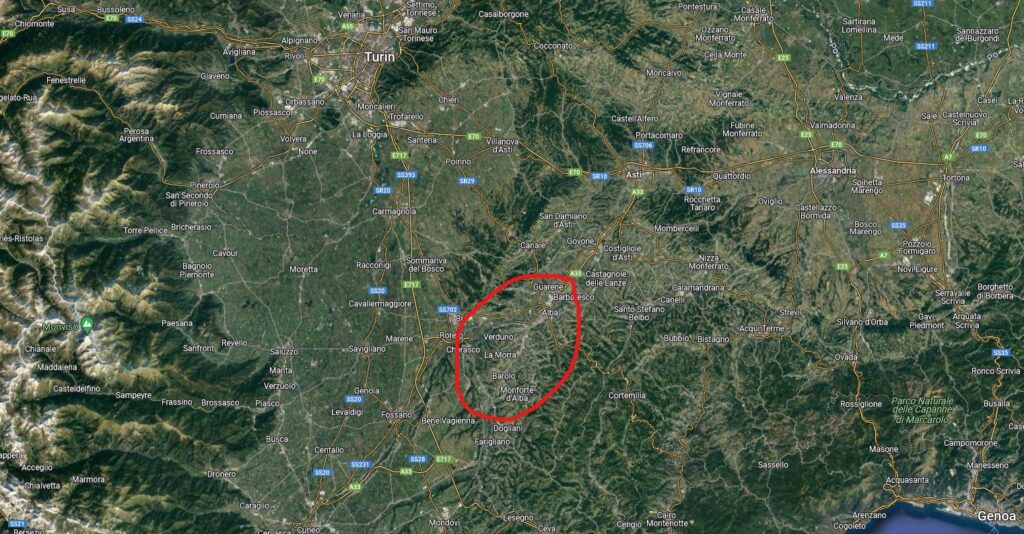

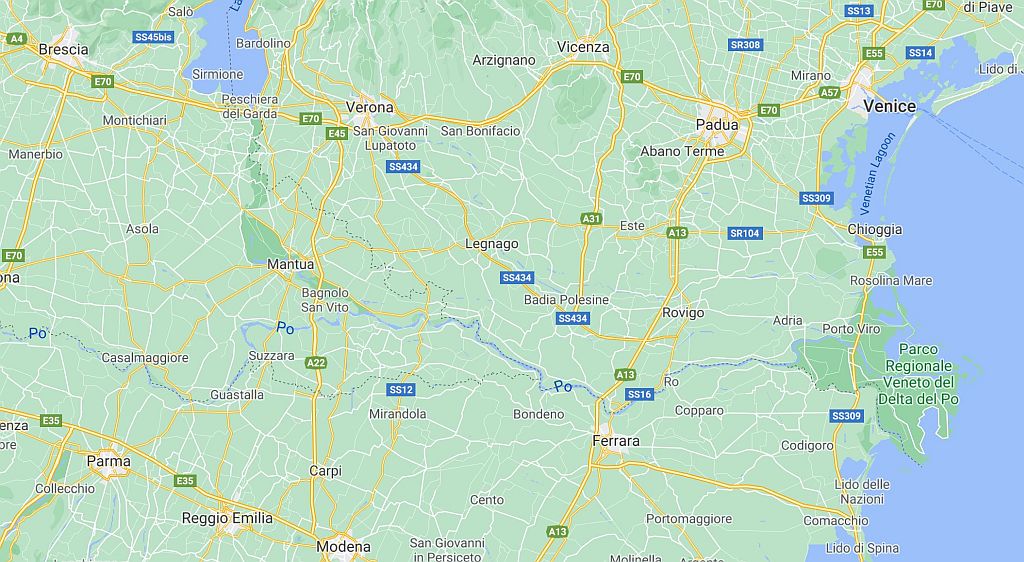

We weren’t sure what to expect, but despite Sardinia being another large island stuck out in the Mediterranean, it didn’t feel like Sicily, and that impression was only strengthened over the next few days as we got to know the place better. Sicily is geologically part of the Apennines, while (as I discovered in the archaeological museum in Cagliari) Sardinia and Corsica broke off from southern France and sort of drifted south-east.

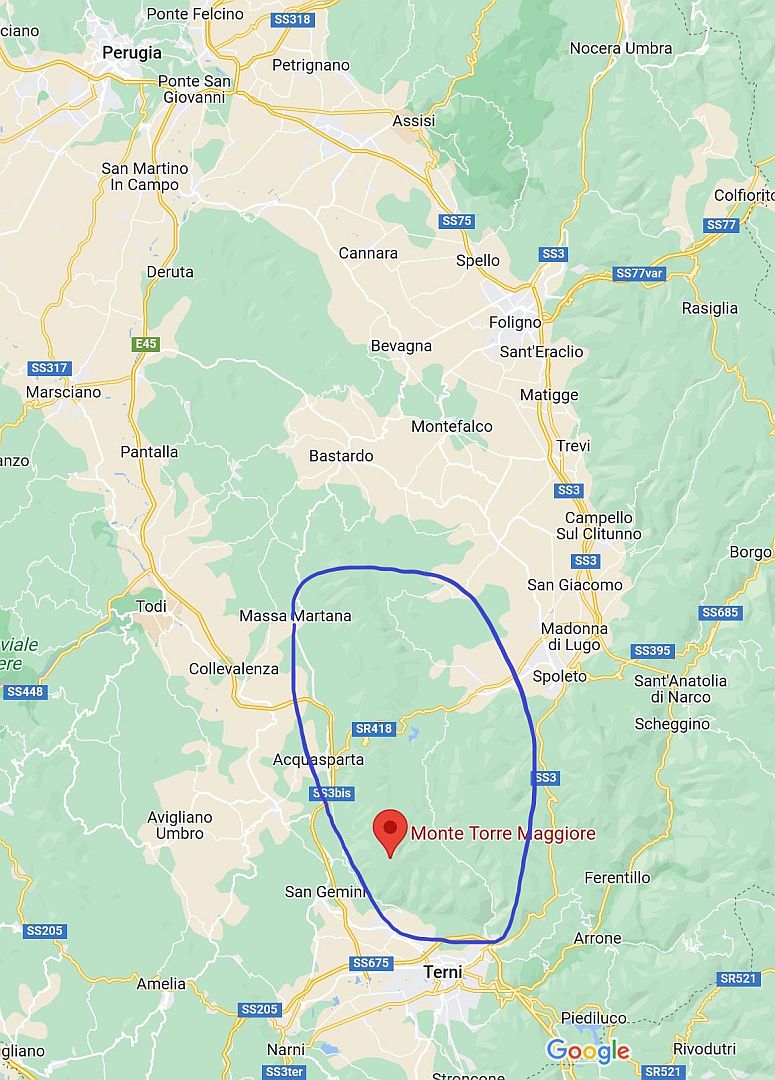

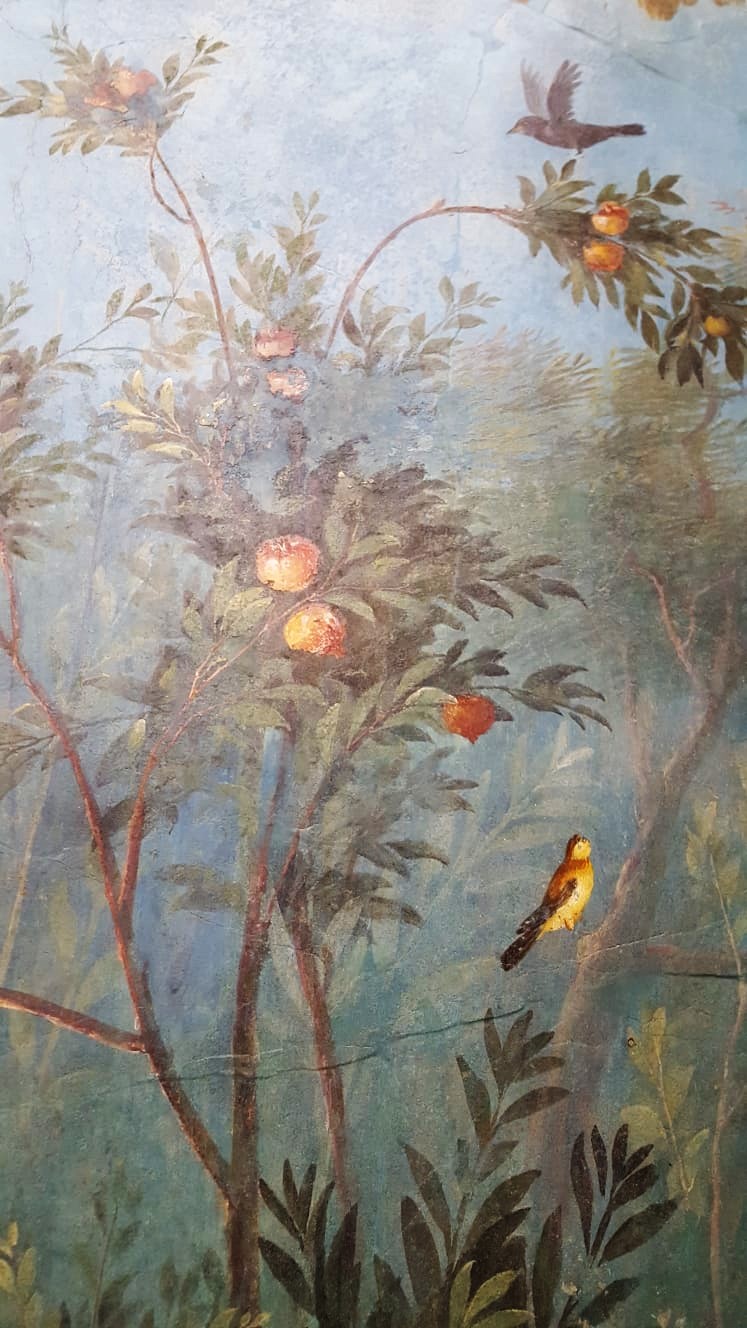

The geological difference means that there are lots of lumps of basalt lying around which lend themselves to building things (of which more in a subsequent article). And unlike the limestone of most of mainland Italy, the basalt of Sardinia means that the tap water is comparatively pleasant to drink. The vegetation is much more reminiscent of the maquis of southern France or the macchia of Italy’s northern Mediterranean coast than anything you would see in Sicily, and while Sardinia’s mountains are not extremely high, they are very rugged and steep, especially in the interior, making manoeuvring difficult for any army trying to establish control, so few did.

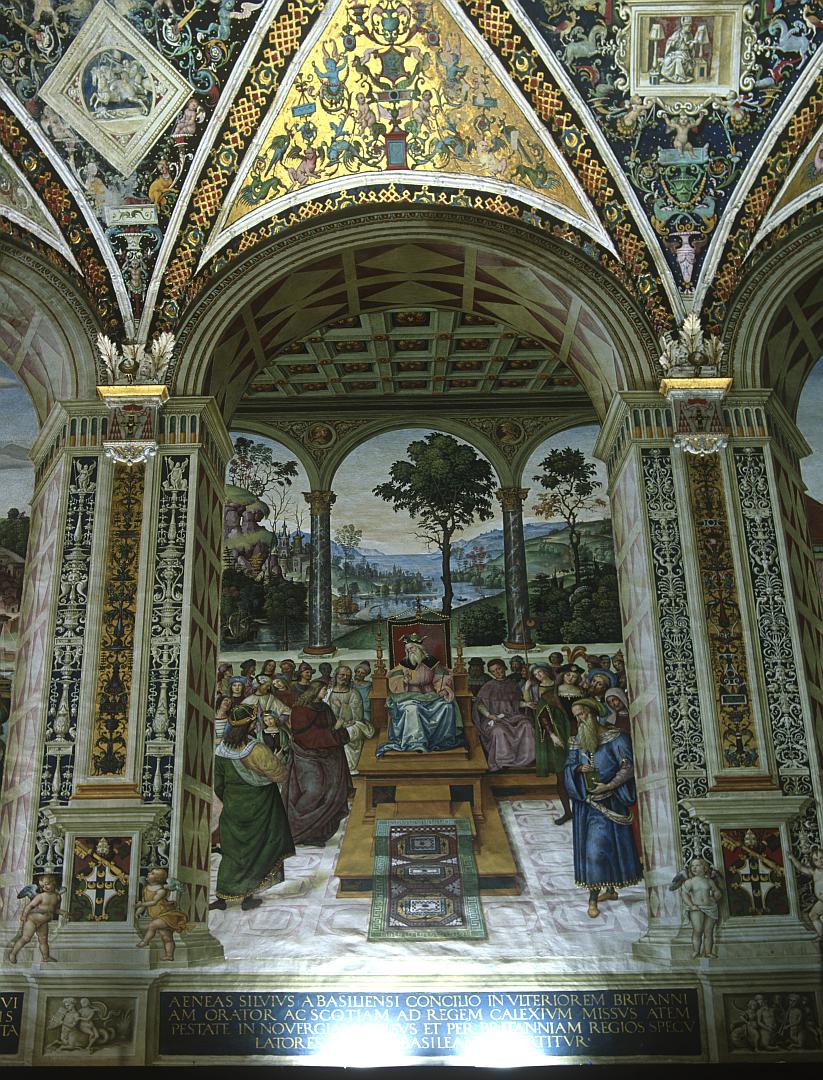

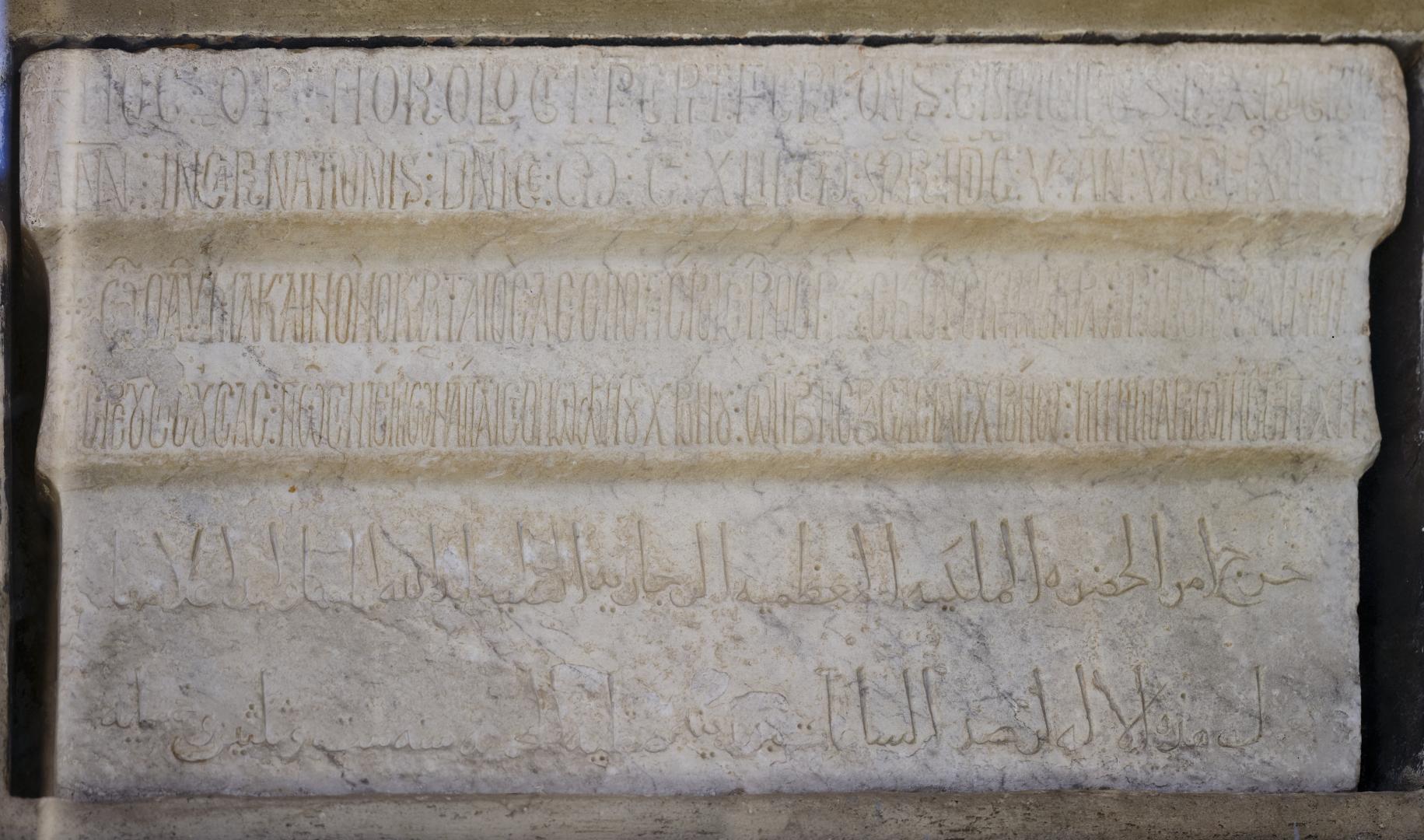

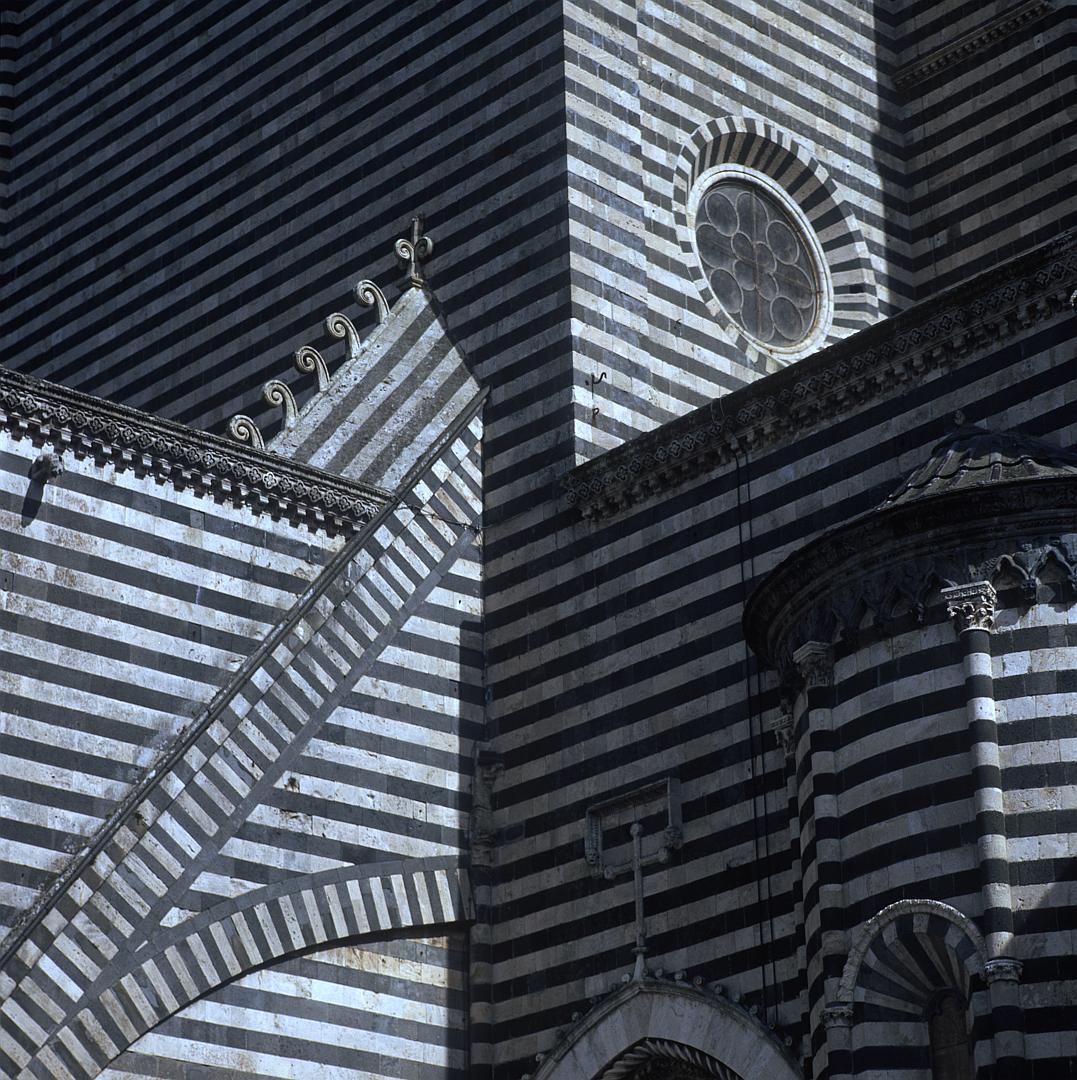

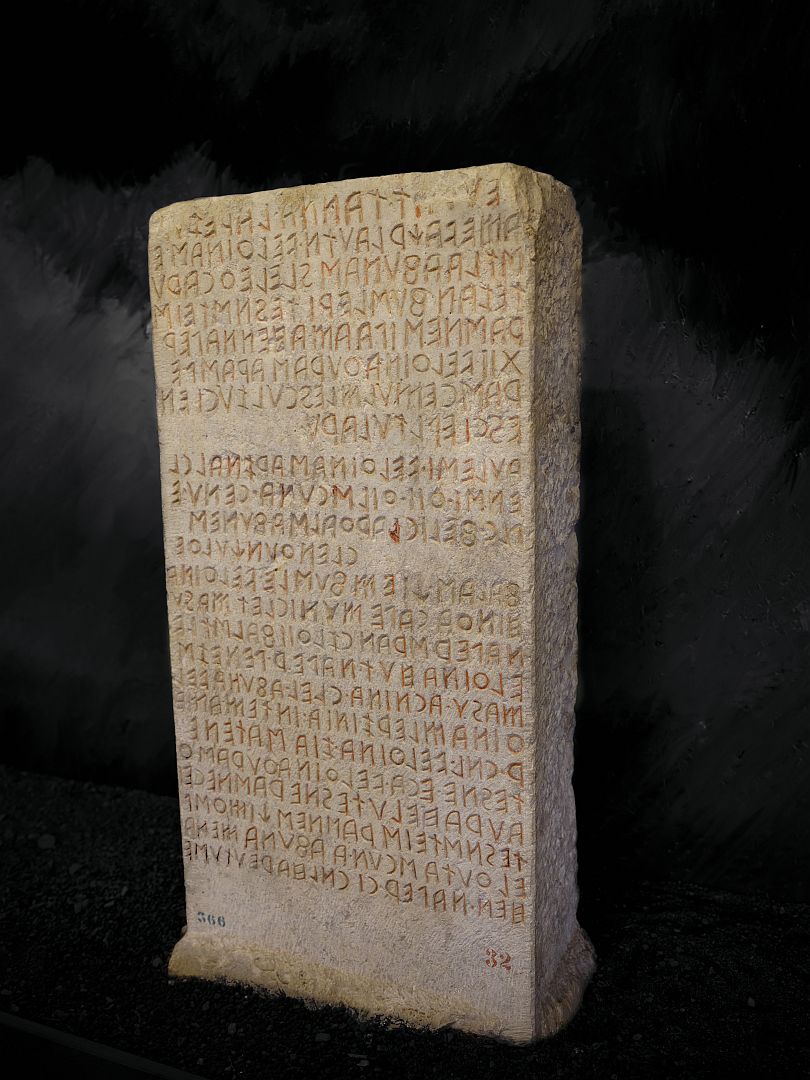

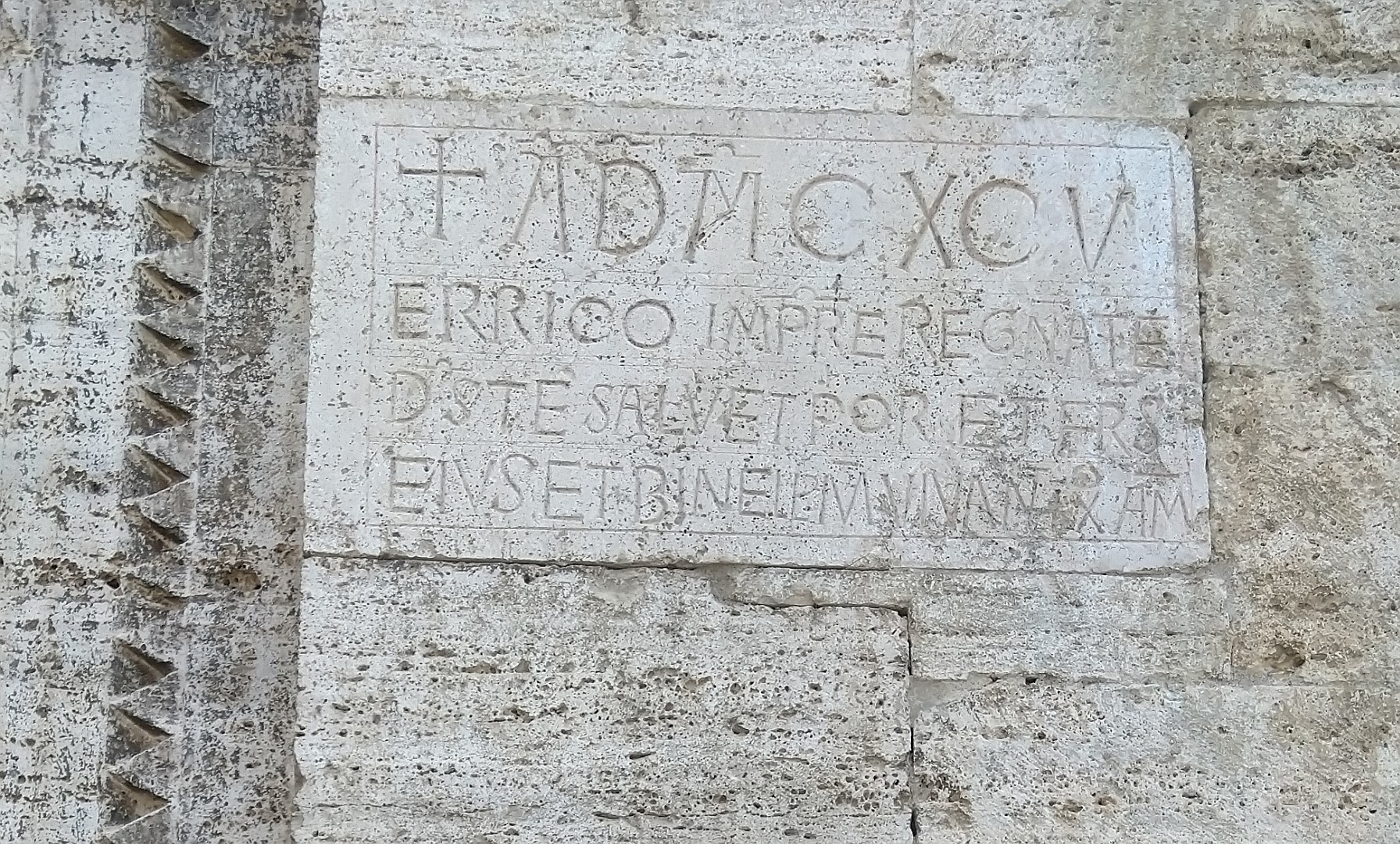

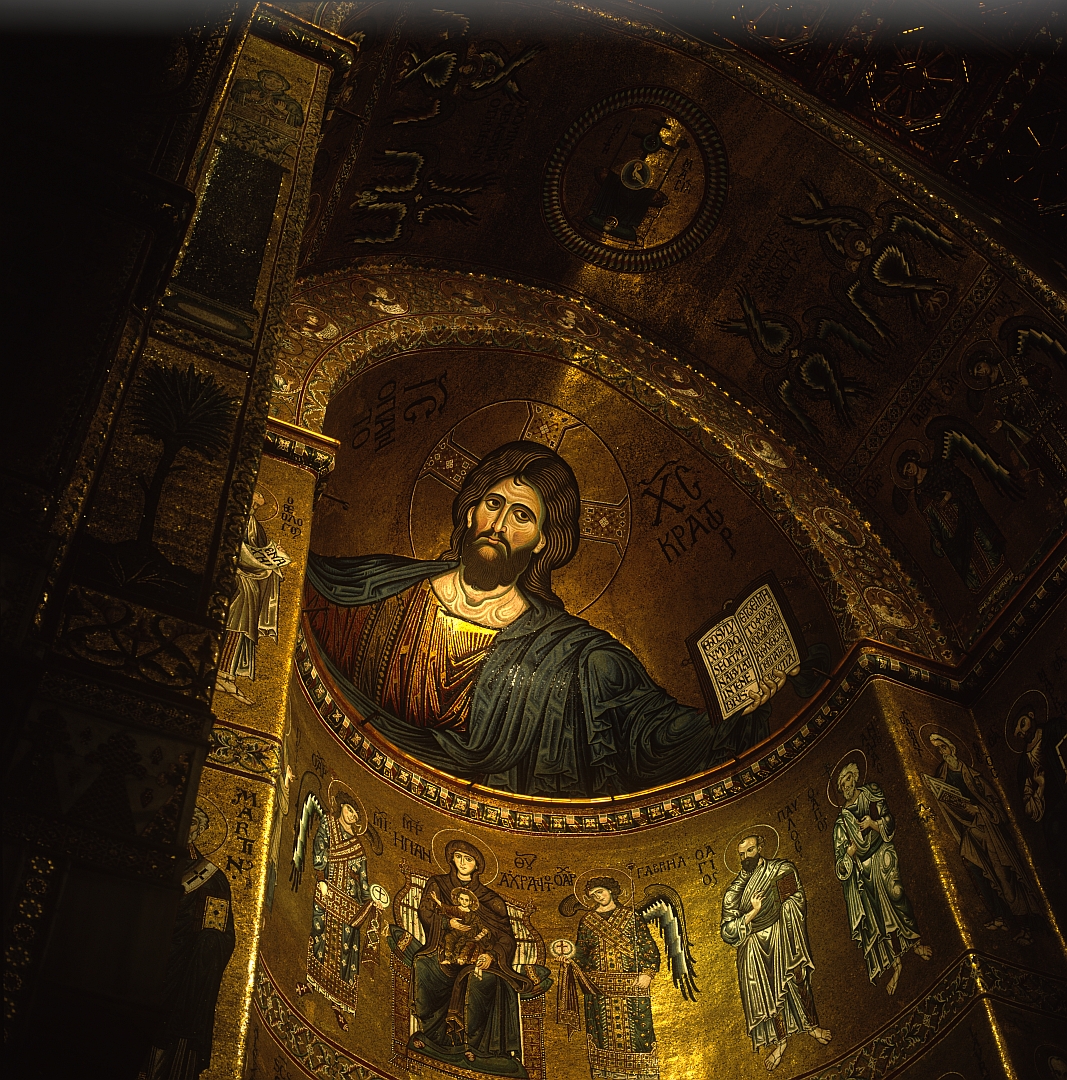

Culturally and historically Sardinia is very different from Sicily as well. Not for Sardinia were the momentous conquests by the Greeks, the Carthaginians, the Romans, the Arabs, the Normans, the Angevins and so on. Instead many Mediterranean powers established towns around the coast, or took possession of existing ones, but these were in effect trading posts for Sardinia’s abundant minerals. In medieval times these outposts – Pisan, Genoan, Aragonese and Catalonian – exerted strong local cultural and linguistic influences. According to our guide book, some of the regional dialects were so different that after Italian unification Sardinians were quick to adopt standard Italian as a means to mutual intelligibility, and that it is for this reason that Sardinians pride themselves on speaking the clearest Italian. We can attest to that. Overhearing people in the street talking to each other or on their phones, it was like listening to the state broadcaster RAI.

Another source of linguistic pride is that of all Italian dialects, Sardo is considered by some to be “purest” in the sense that it is closest to vulgate Latin. I’m not sure how that squares with the idea that there was so much linguistic diversity, but no doubt there is a coherent path through it all. As in other areas of Italy, the monoglot policy of previous eras has been replaced by official endorsement of Sardo in the form of duplicate place names and street signs. How much effect that will have remains to be experienced by future generations, but Sardo is is definitely identified with regional politics – political posters often use it instead of Italian. And on a bilingual Italian/English information sign outside a church, someone had placed a sticker over the Italian text which read “e in Sardo?” (“and in Sardinian?”).

History also took Sardinia on a different path into the unitary state of Italy. Before unification Sicily was part of the deeply conservative southern kingdom of the Bourbons, ruled from Naples. Sardinia was part of the state of Piedmont, comparatively forward-looking and aligned with northern European countries like France and Britain. And when Italy was finally united, it was under the Piedmontese, so Sardinia was on the winning side, in a sense. How much notice the shepherds in their remote mountains took of all this is another question.

Sardinia has a reputation for truly awful roads, and this is completely deserved. The one decent road is the main north-south highway, still called the “Carlo Felice” after the king who commissioned it, but everything else is pretty bad. One learns to watch the car ahead as it weaves between patches of broken tarmac, and to adapt accordingly. At one point I put the left front wheel of our leased Peugeot into a monstrous pothole. I was sure that I had inflicted some mortal injury on the car, but it seemed OK. The next time we took that route we kept a lookout for the pothole and successfully avoided it, but I had noticed a tow truck following us. Sure enough, a couple of hundred metres past the pothole an expensive Mercedes was pulled over with its hazard lights flashing, and the tow truck pulled in behind it.

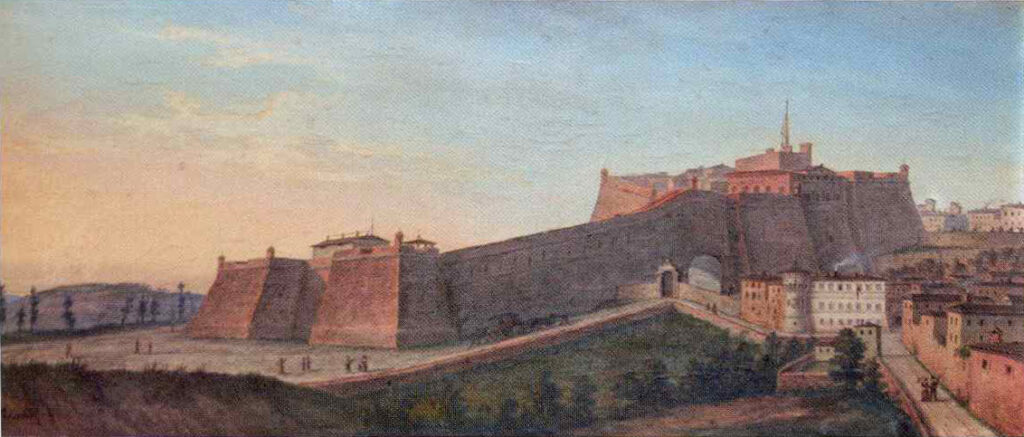

Cagliari

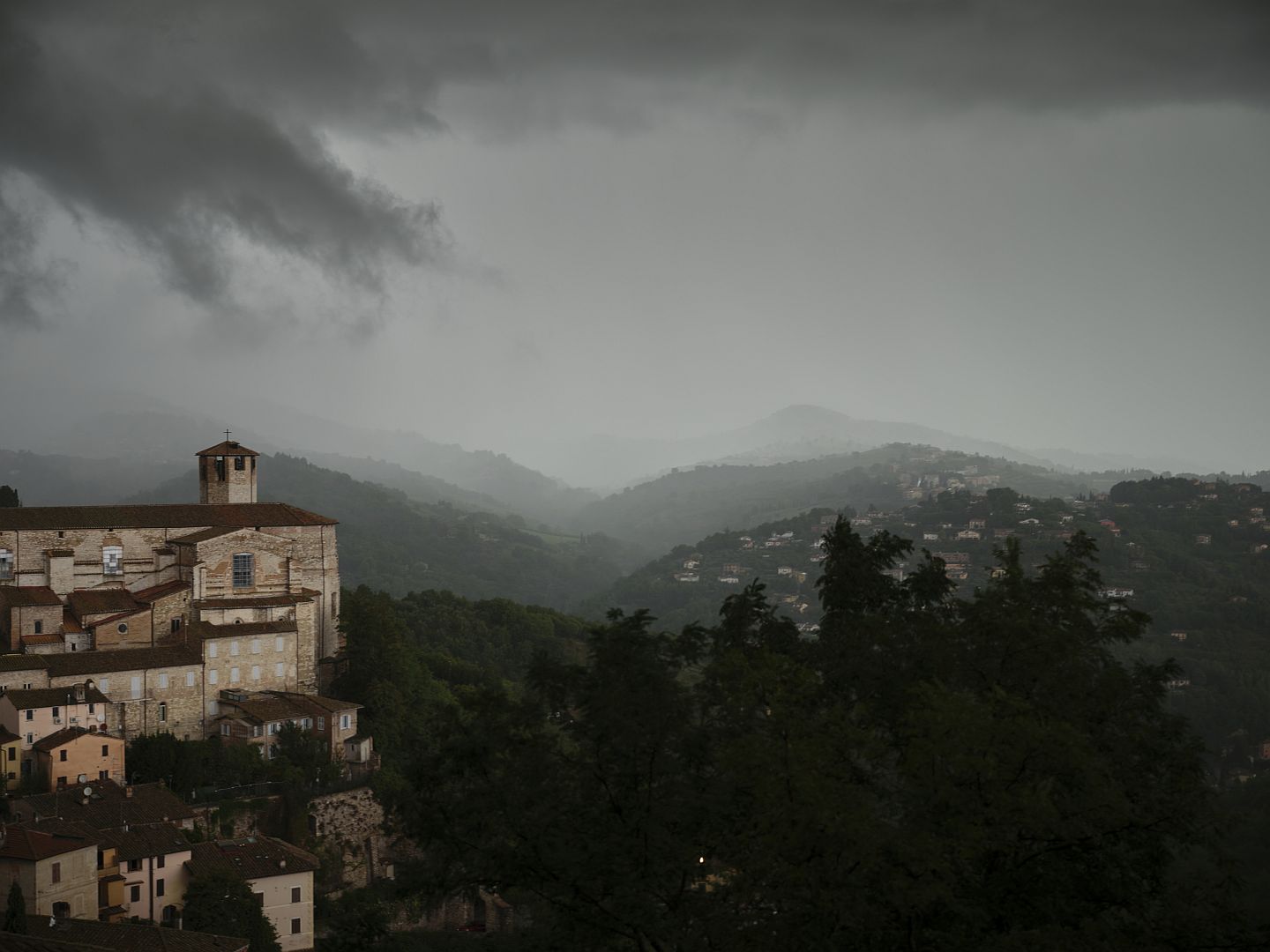

The capital city of Sardinia is not blessed with a spectacular setting. Certainly there are distant mountains on three sides, and the sea on the fourth, but closer by are salt pans, an oil refinery, power stations and wind farms. In the centre of the old town is a modest hill called the Castello on which was the old fortress. Unfortunately during the war Cagliari was a major naval base and was severely bombed as a result. Much of the inner town is therefore rather ugly postwar reconstruction.

It must also be said that Cagliari has a rather severe graffiti problem. That’s a problem in most Italian cities these days, but in most the graffitists avoid the older monuments. Not here, alas. Some of it, especially around the university, is political. Some is ironic comment in the tradition of Italian pasquinade; at a lookout over some soulless 1950s buildings, one graffito says “bel cimento, no?” (“nice concrete, eh?”). But most of it is unoriginal and destructive.

The Festa di Sant’Efisio

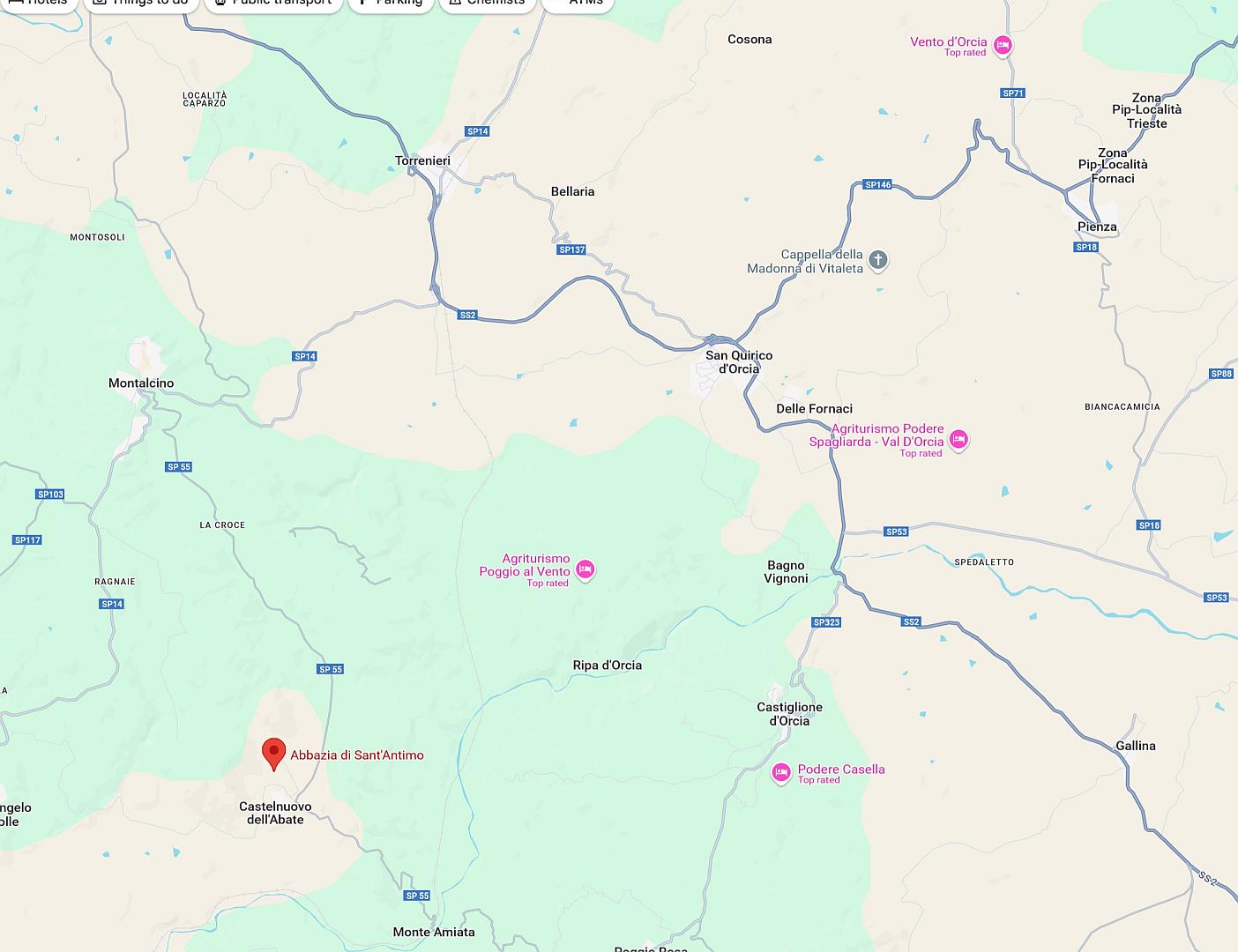

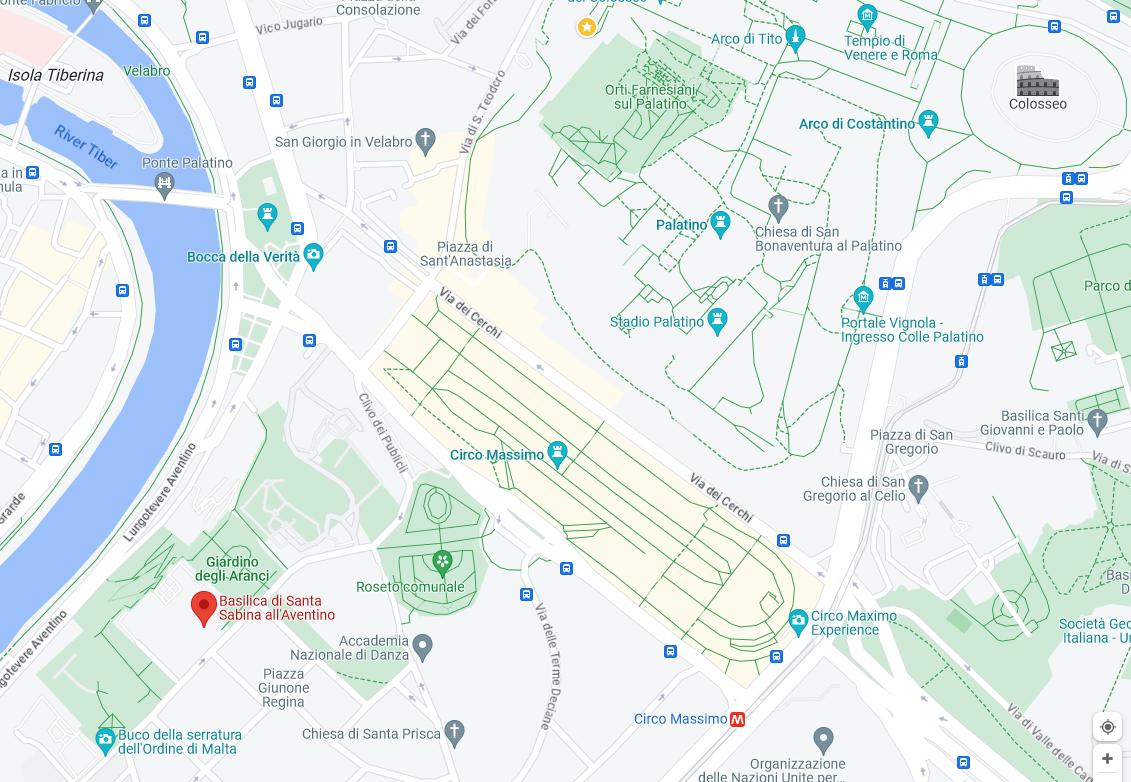

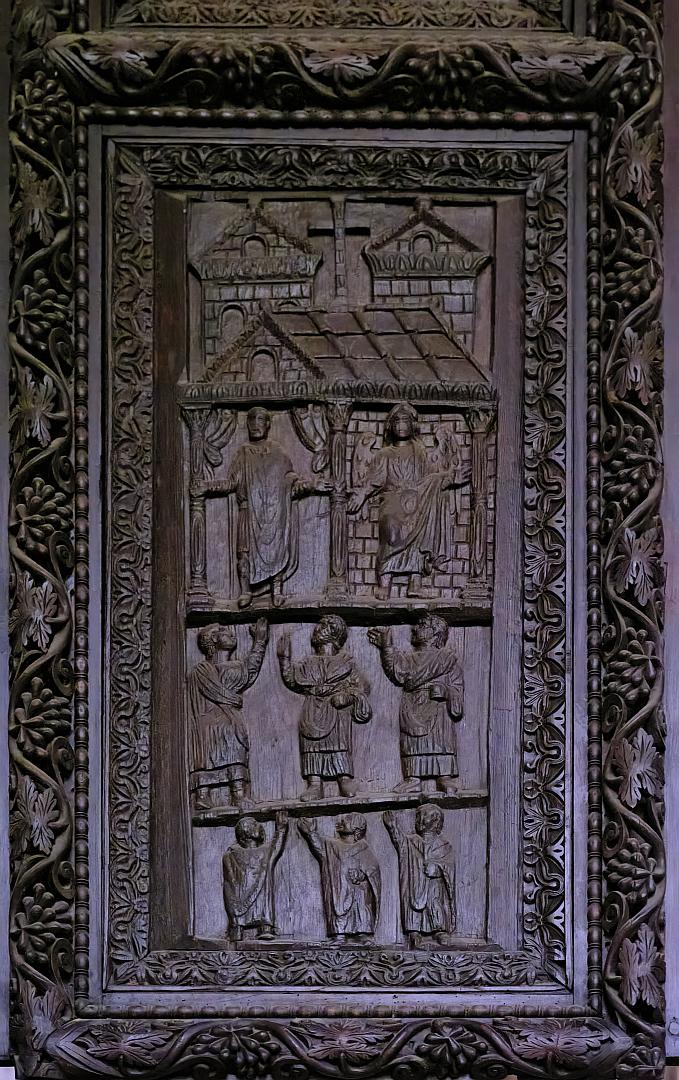

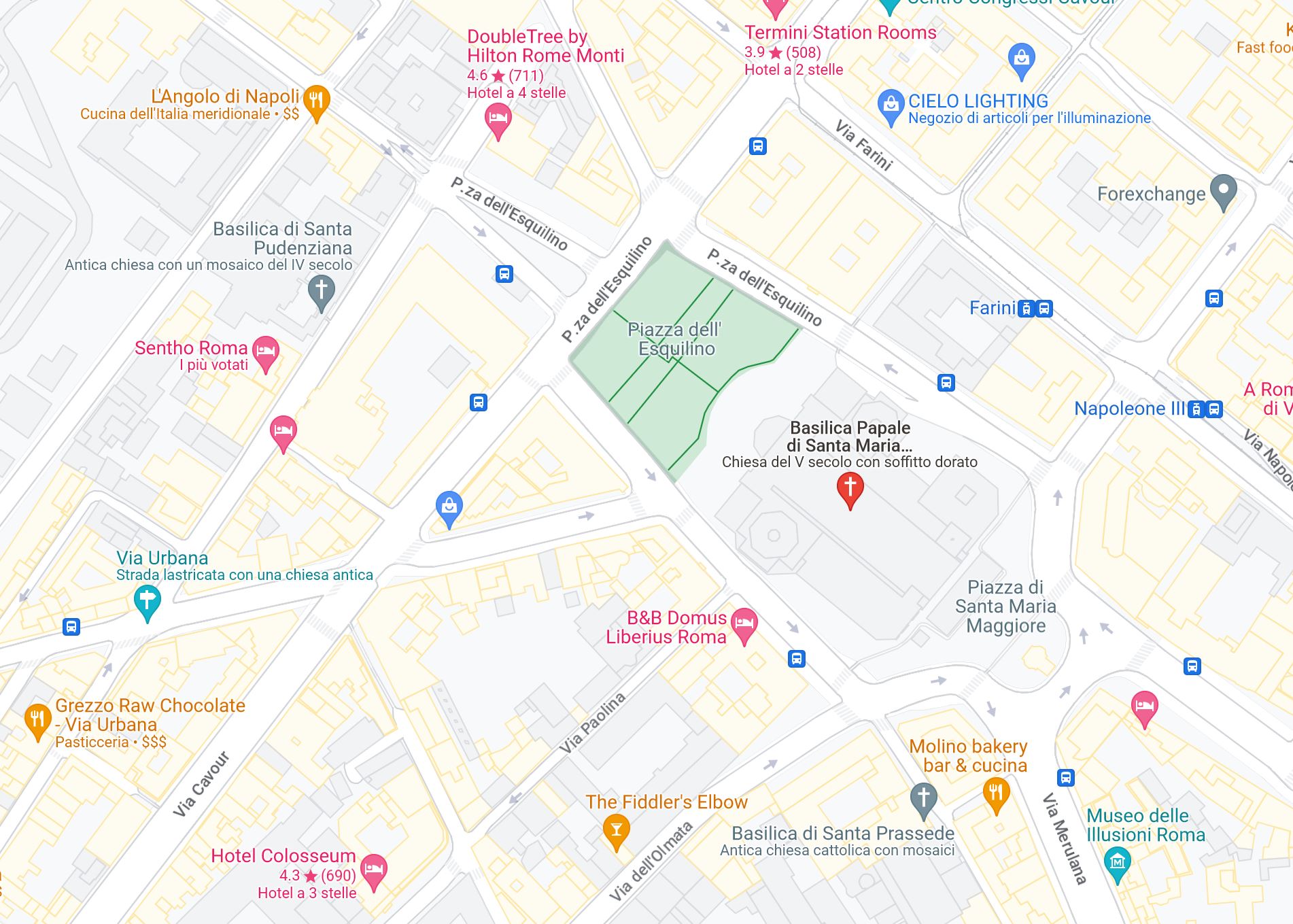

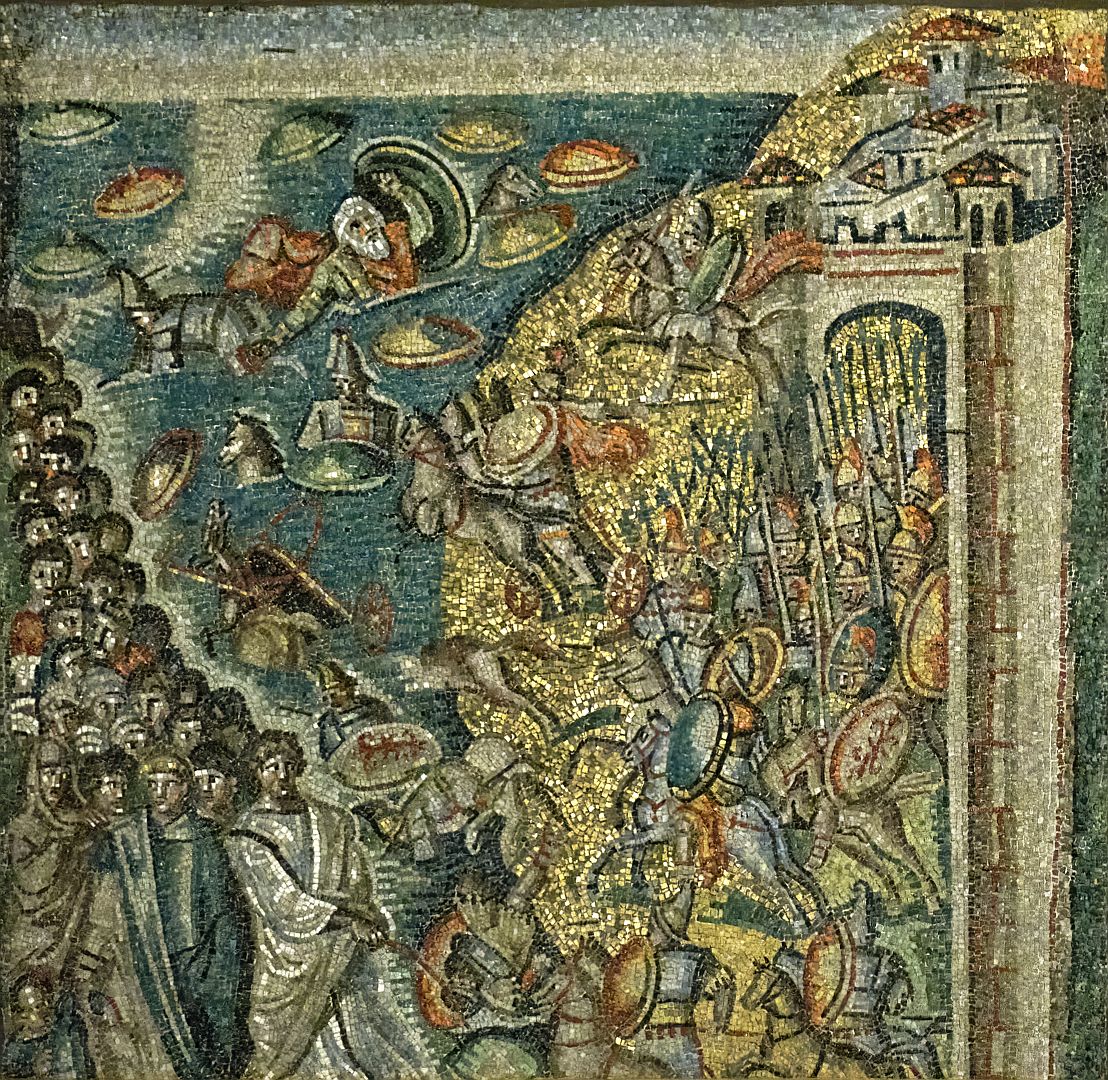

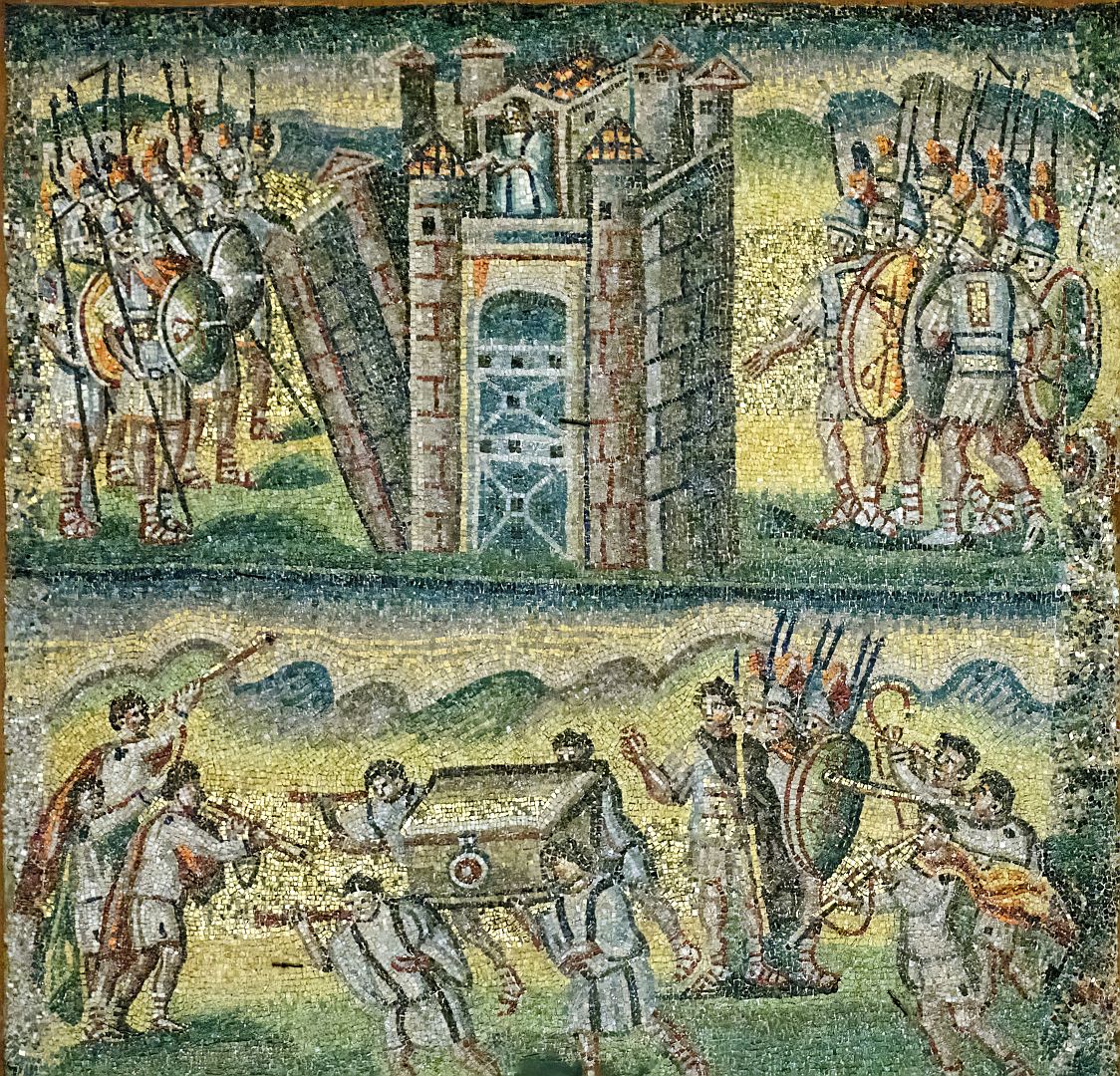

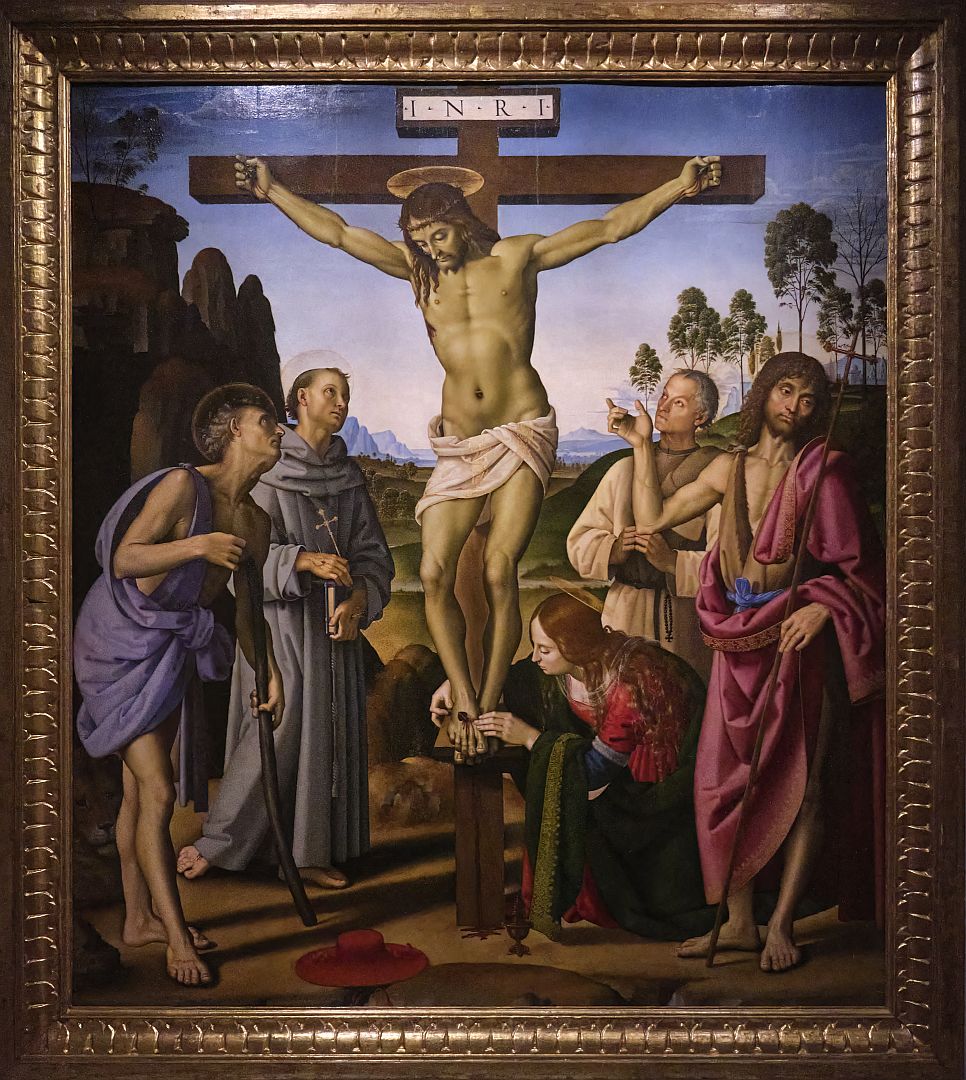

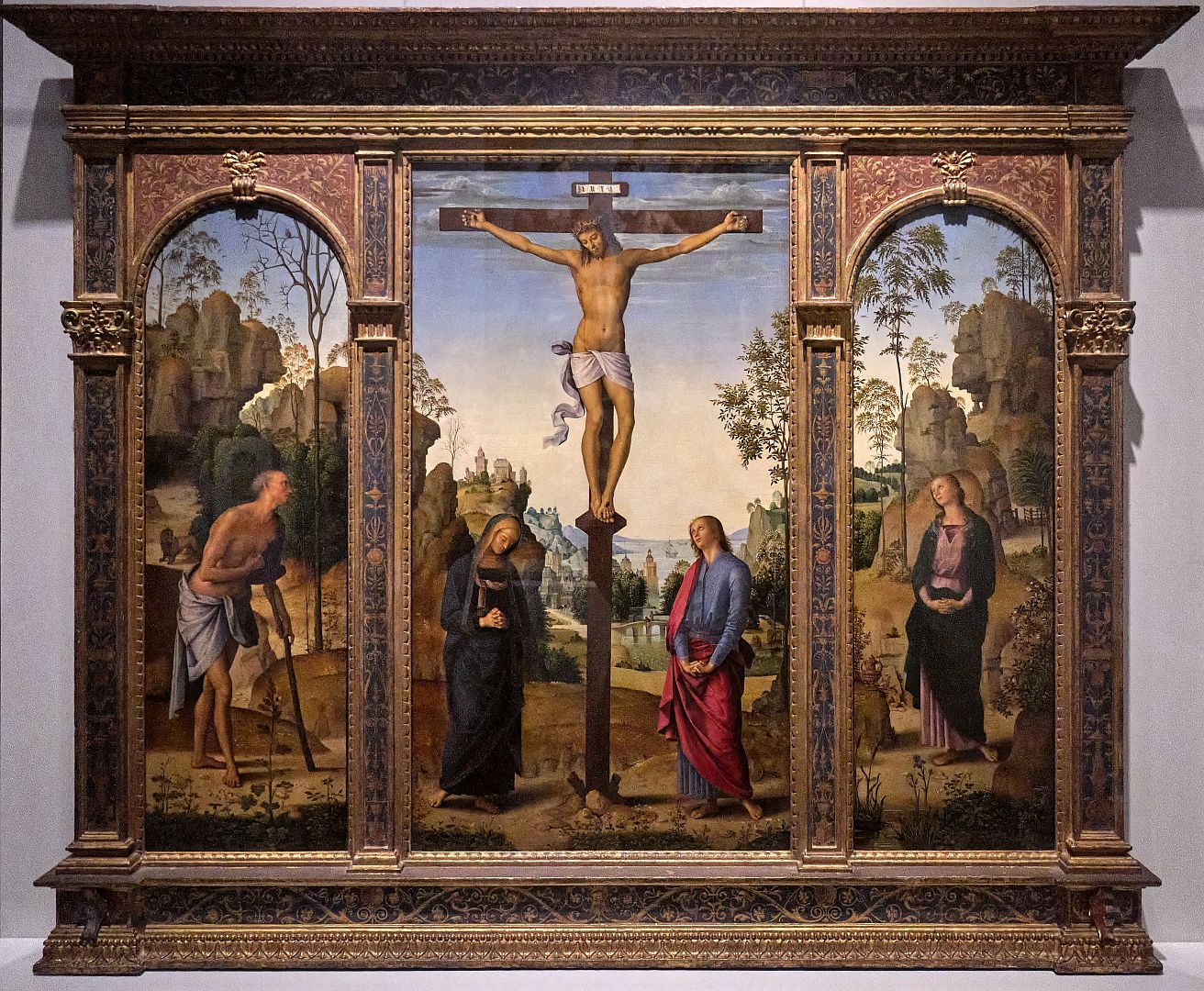

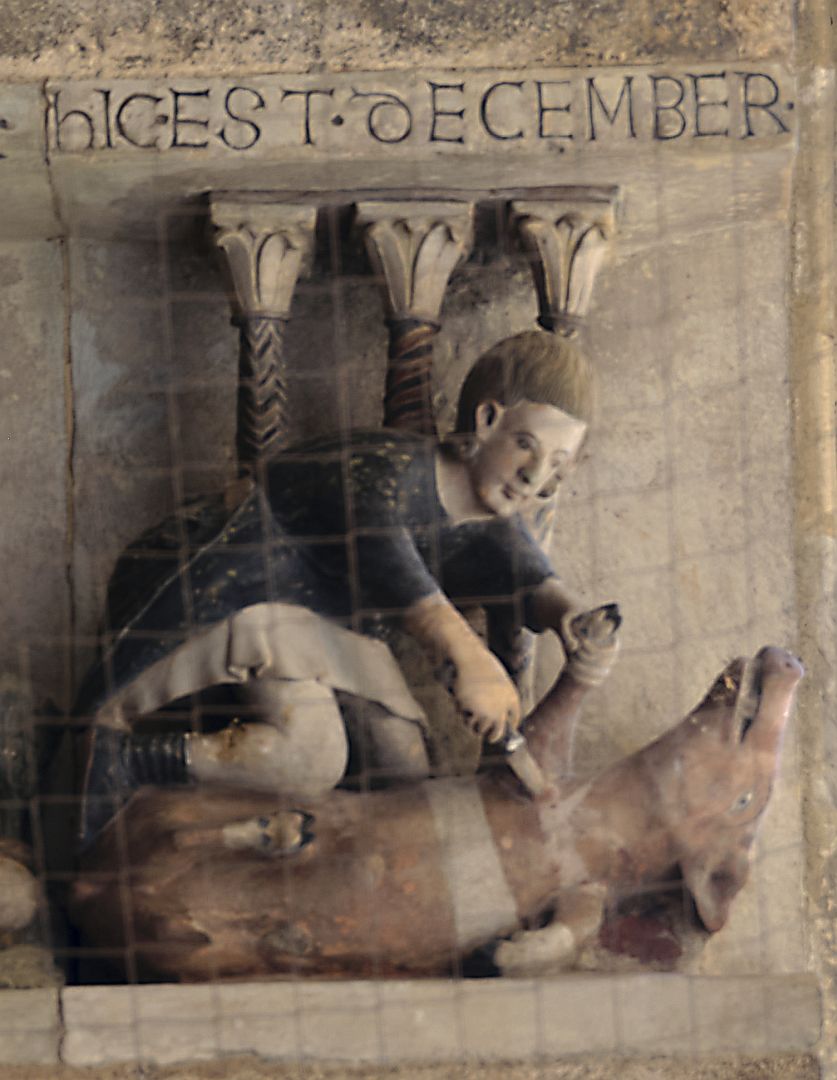

But nonetheless we wanted to come here, and were glad to be here on the 1st of May, because that is the feast day of Cagliari’s patron saint, Sant’Efisio, when there is a spectacular parade in his honour. Not one of the better-known saints elsewhere, Efisio was apparently a Roman soldier from Antioch in Asia Minor called Ephysius who was posted to Sardinia and martyred at a place called Nora a few miles from Cagliari during the persecution of Diocletian. And that’s it. History tells us nothing else about him, but that is enough for the Cagliaritani and indeed the rest of the Sardinians to have adopted him as their own. His statue, in the church dedicated to him in Cagliari, shows a cheerful-looking fellow in ornate armour with curly light brown hair and a neat little moustache and goatee beard.

But obscure as he may be, the Sardinians throw a huge party for him every year, with what is said to be the longest religious procession in the Mediterranean. It was certainly long – it took about two and a half hours to pass.

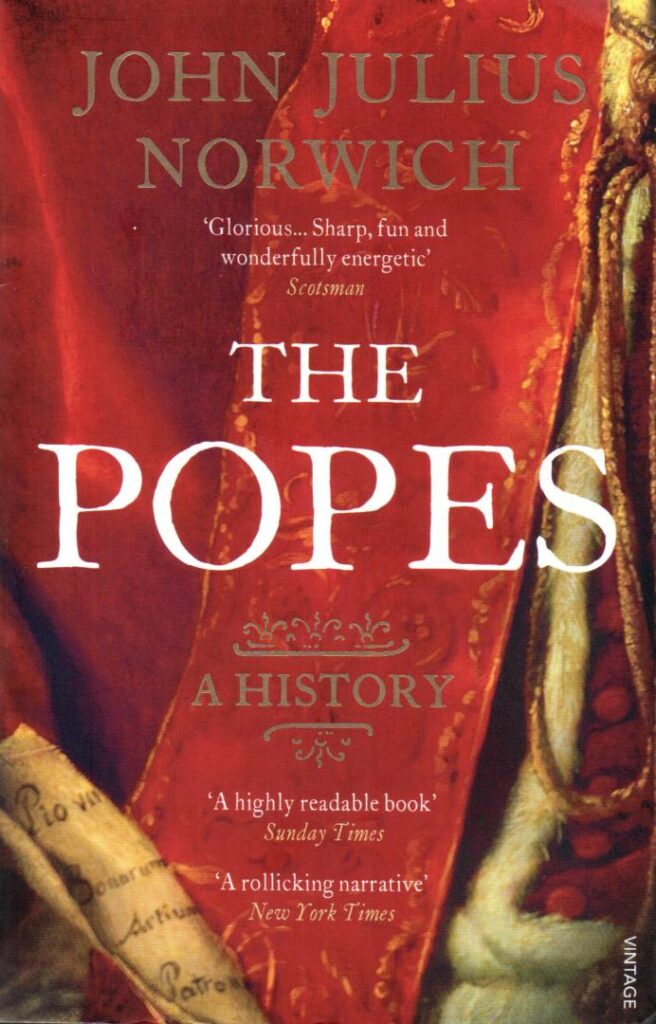

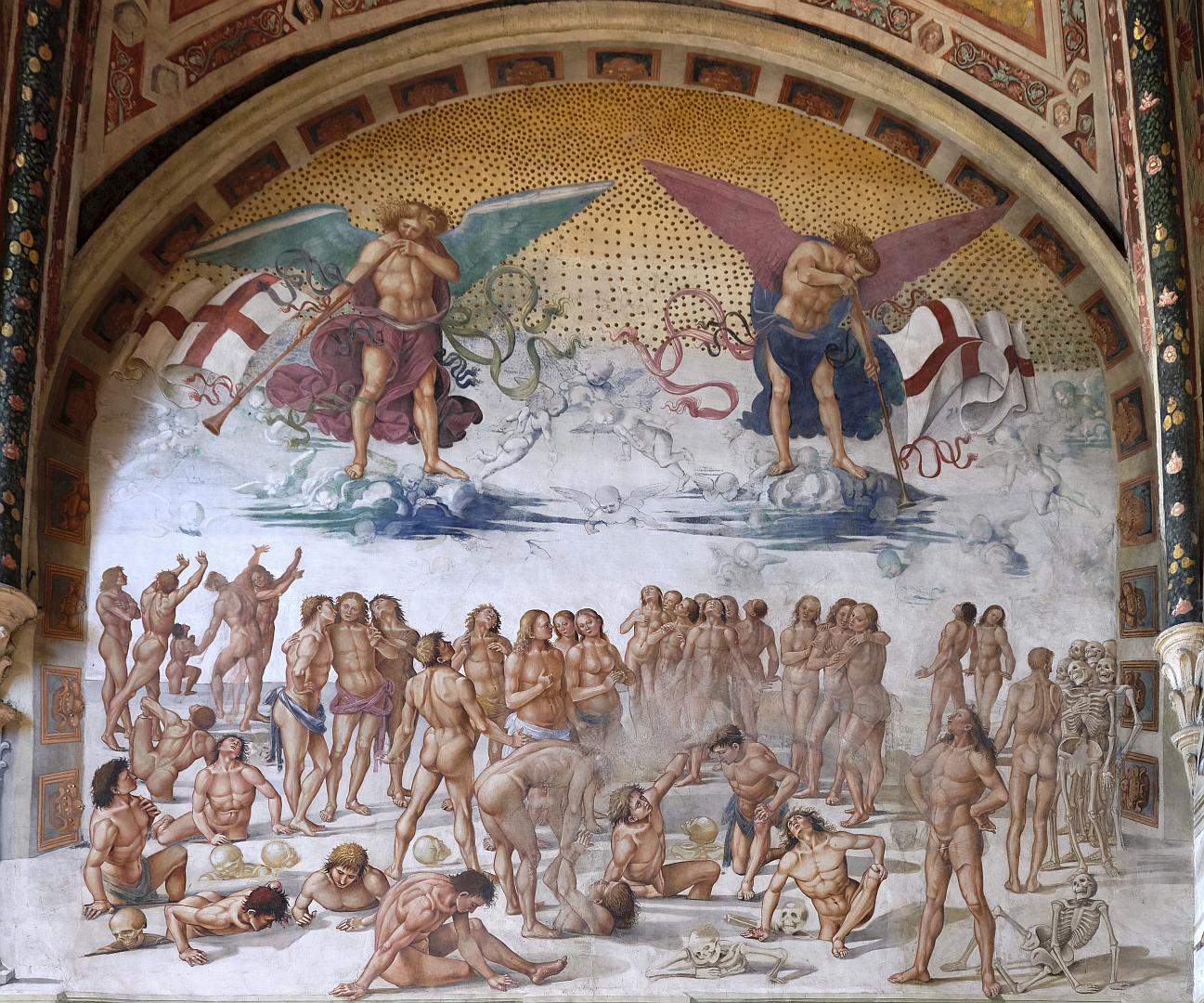

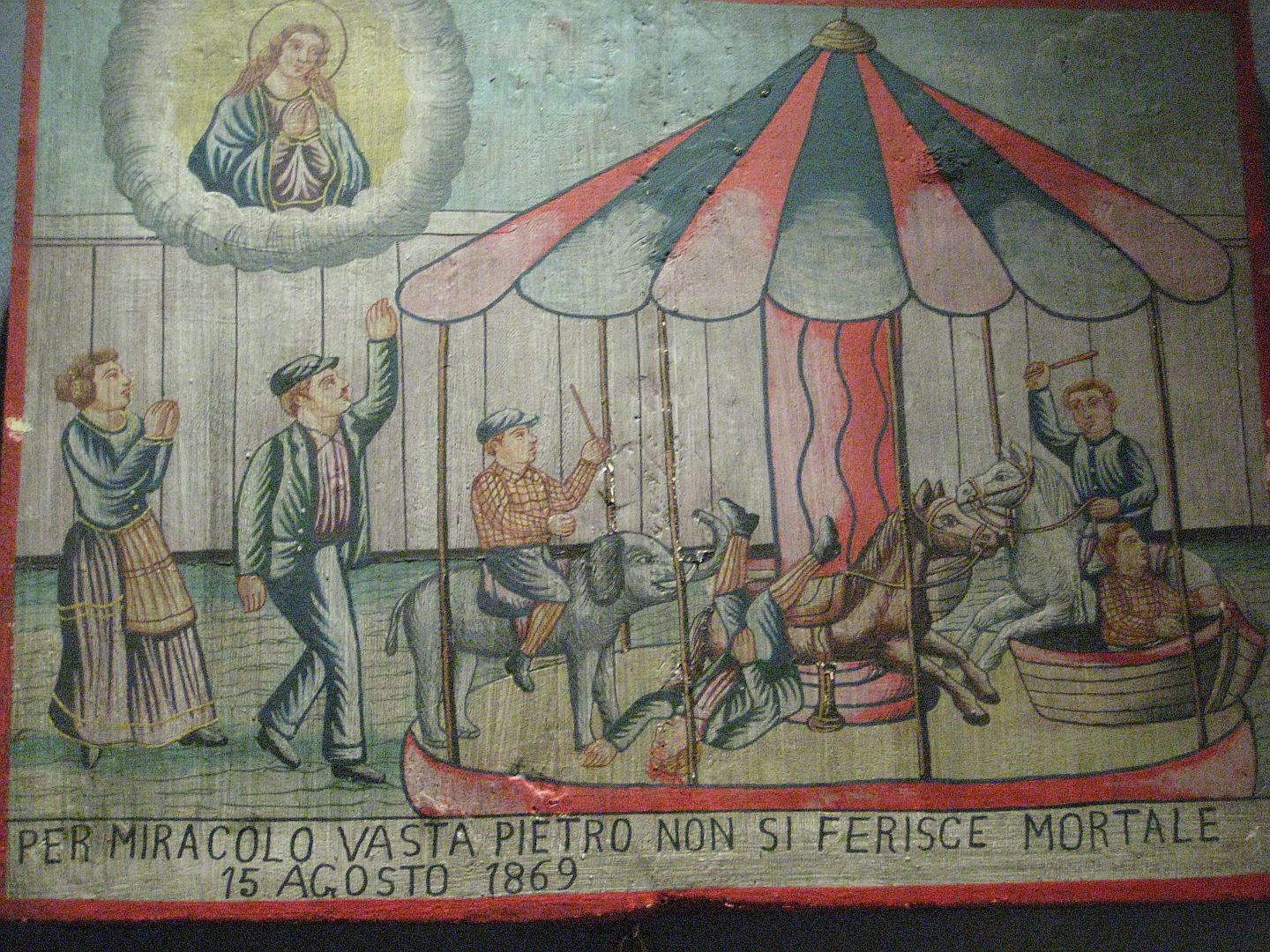

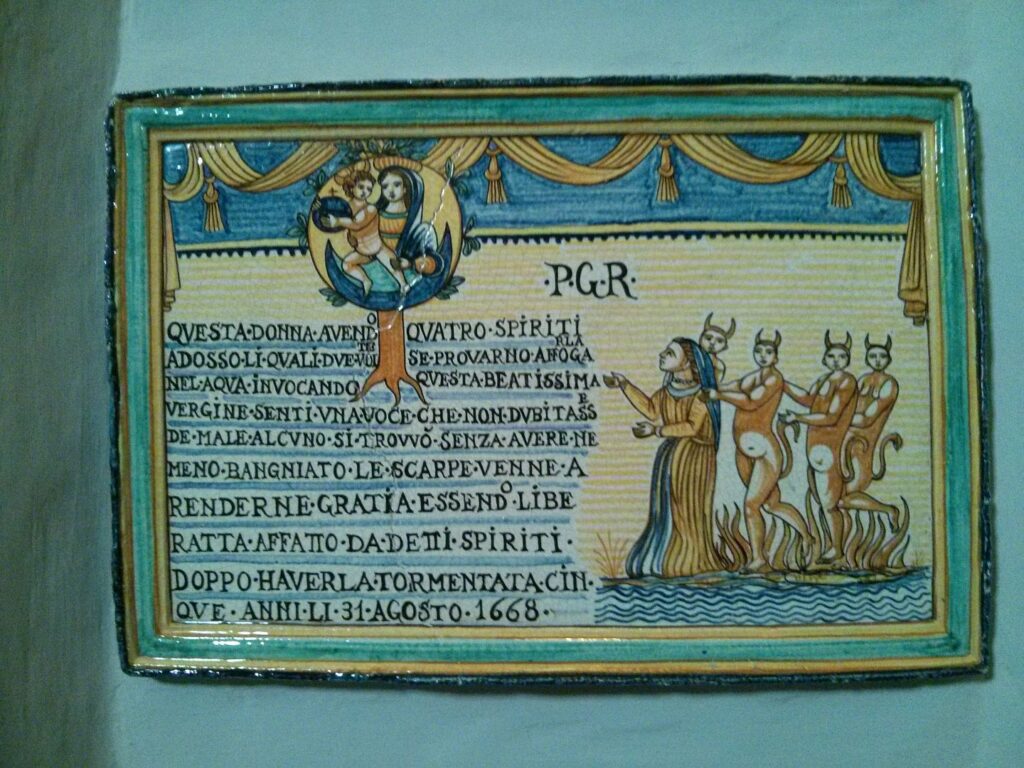

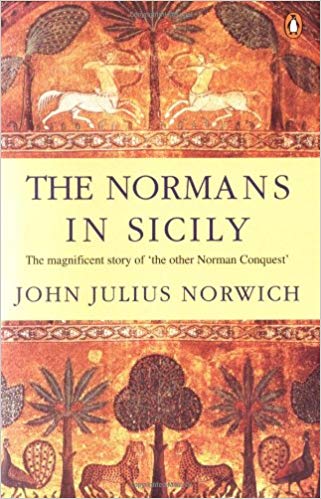

As I discussed in The Serious Business of Dressing Up, many such processions elsewhere are comparatively recent revivals going back to perhaps the 1980s at most. Of course statues of saints have always been carried about town on their feast days, but as for lots of people dressing up in historic costumes of varying degrees of authenticity, that’s a more recent thing.

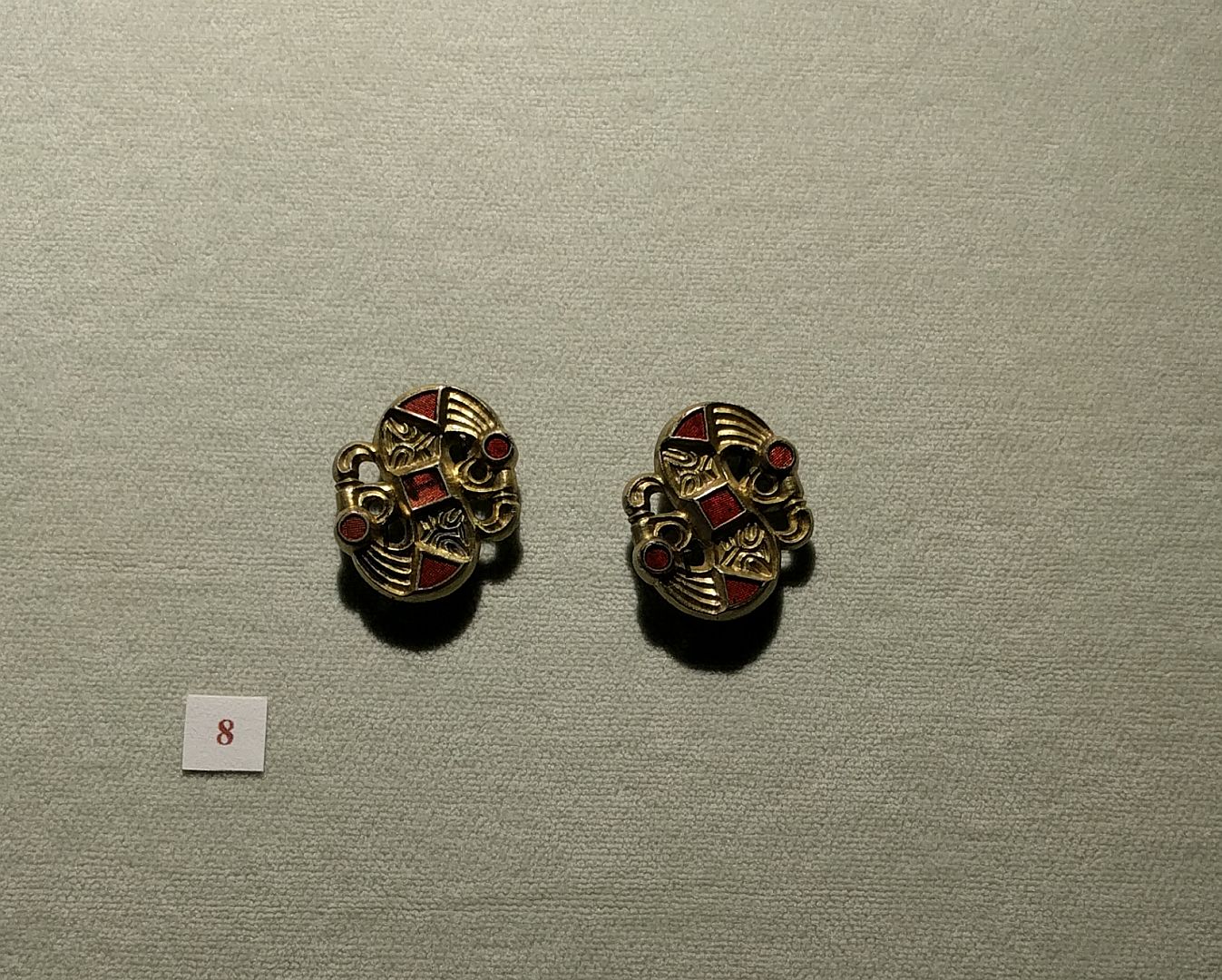

Not here. The Sant’Efisio parade is a genuine survival, and what’s more the costumes are not based on the participants’ own somewhat elastic interpretations, but are the traditional dresses worn by men and women from towns and villages all over Sardinia. The contingent from each place walk (or ride) together, and the costumes they are wearing are those proper to the town or village. And they are extremely ornate, especially the women’s ones. A few days later we visited an ethnographic (ie folk) museum in a town called Nuoro in central Sardinia. The costumes there, whether from the 1950s or the 1850s, could have been those worn in the parade.

The male costumes are mostly fairly similar – white blouses and baggy pants with a black, embroidered or coloured waistcoat or tunic and black gaiters. Sometimes the tunic is extended to become a sort of kilt. Sometimes the kilts are separate. They wear tubular hats, usually black, which are folded or rolled in different ways. Some shepherd costumes featured a coat made from the hide of a sheep that looked as it would have been very warm on a cold and wet mountain top, although less suited to a sunny day in Cagliari in May. There were also some very exotic-looking fellows in orange jackets and orange flower-pot hats who looked very oriental, like Ottoman Bashi-Bazouks or something, but the Ottomans were one of the few Mediterranean cultures not to have touched Sardinia, so I can’t explain that.

The female costumes, on the other hand, were of a beauty and variety that defy description, so you will have to look at the photographs. I say “variety”, but the variety is between places, not within them. Every lady (and young girl) from the same place was dressed similarly. I guess that if you want to wear something very different, you have to move to a different town. According to the ethnographic museum, these dresses were wedding dresses as well being as for special occasions.

Some of the ladies’ dresses seemed like something rather avant-garde from a Milanese catwalk. These involved the hem of an outer layer of the skirt being lifted up and turned into a sort of hood.

Even before the saint or any clergy appeared, the religious nature of the festival was apparent. Participants sang hymns, many of the ladies (and a few men) carried rosary beads, and a few men walked the cobbled streets barefoot while carrying crucifixes.

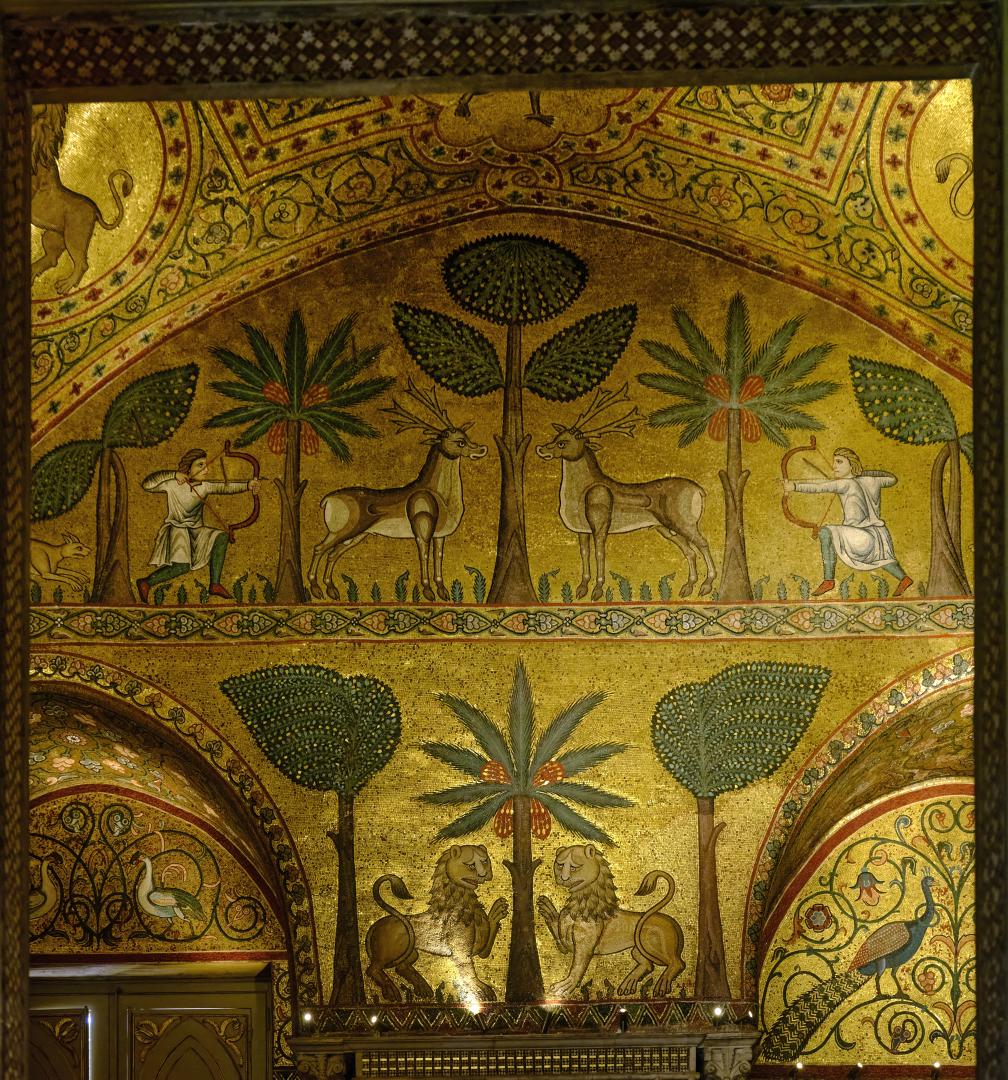

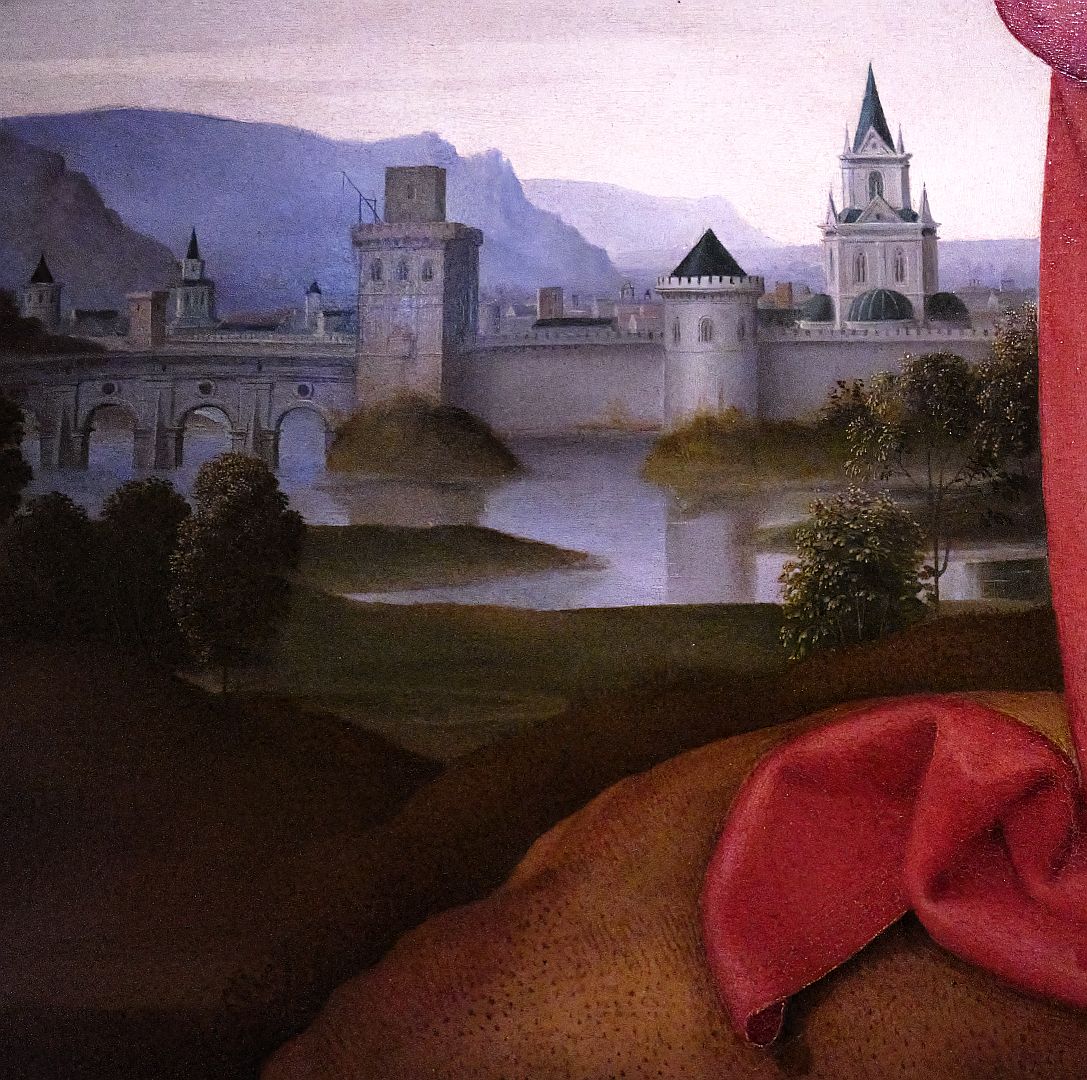

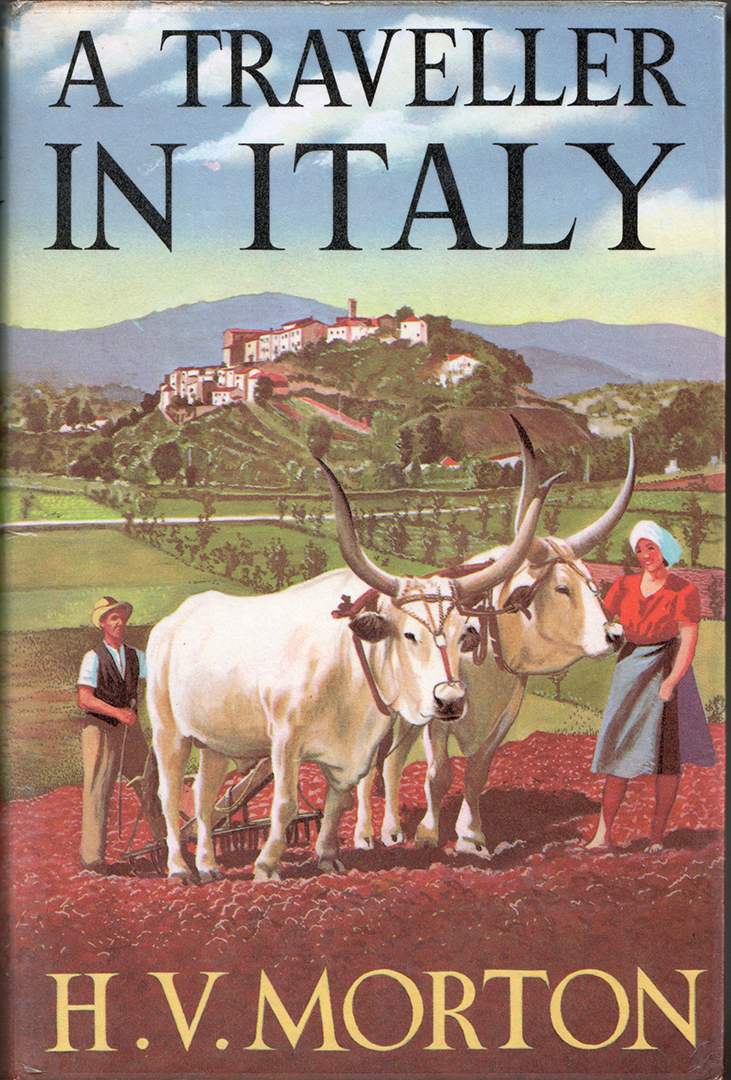

The parade was led by highly-decorated carts drawn by oxen (also decorated). These enormous beasts, hugely powerful but very patient and placid, would once have drawn ploughs but although that job has presumably been taken over by tractors, I’m glad people keep them around for this sort of thing.

The carts were decorated with flowers, some artificial but many natural, which makes the point that this is a sort of spring festival as well. Each cart carried the name of the town it came from, and many of the people on the carts were singing hymns.

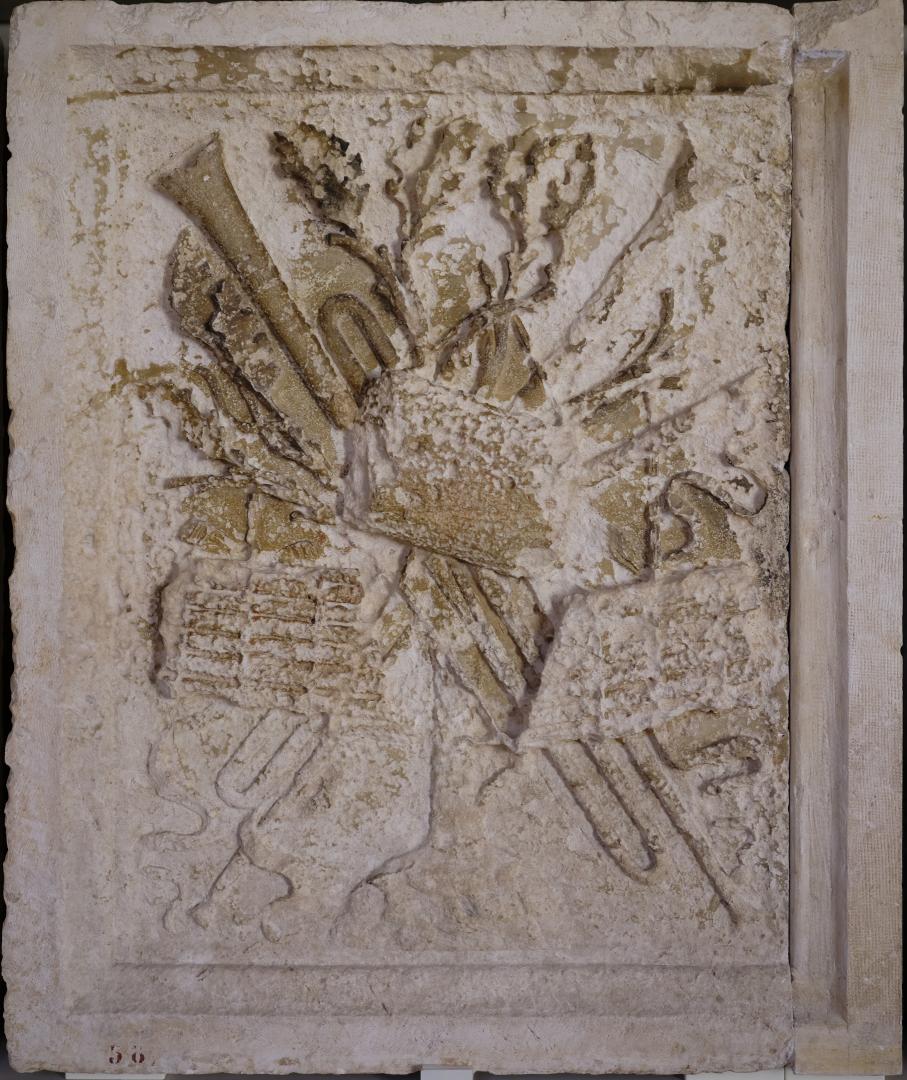

The singing was in unison rather than harmony, but often men and women would take alternate verses. The singing style was quite nasal and very penetrating – useful for calling across mountain valleys, no doubt, but not unpleasant. There were instruments too – mainly a sort of double-reed thing. We thought these surprisingly loud for their size and shape, until when I was processing the photographs on the computer I noticed that some crafty fellows had taped microphones to them and had battery-powered speakers attached to their belts.

After the carts came a large number of groups on foot, each preceded by a sign saying where they were from, and when the contingent from each town or village came in sight there was an excited cheer from their fellow-citizens in the crowd.

After the pedestrians came a number of groups on horseback. Initially these were dressed like the pedestrians – the women in gorgeous dress sitting side-saddle, and some of the men carrying enormously long muskets – and then some chaps looking as if they might have charged with the Light Brigade; presumably in uniforms of the pre-unification Piedmontese military.

Eventually the saint’s effigy appeared, and a large section of the crowd joined in behind it. The festival officially goes for four days, with the saint’s effigy progressing to the little church at Nora that marks the traditional site of the his martyrdom. As it makes its way along the coast there are mini-parades put on by local communities. But most of the participants in today’s parade would have taken the rest of the day off; no doubt there were some very sore feet, especially among the ladies who had covered the whole route in high-heeled shoes. Despite that everyone looked as if they had enjoyed themselves and by the sound of it quite a few people partied well into the evening.